After a long day at the lab bench, spent poring over microscope slides or crunching numbers into results that hopefully make sense, there are few things as cathartic for Lorenzo Washington as grappling with his opponents at judo practice. “It uses my brain in a different way than science does,” he said. “I’m not actively thinking as much as I’m reacting, listening to what my body knows.”

An unarmed modern Japanese martial art, judo emphasizes free sparring. “It’s all about technique and using your opponents’ movement and strength against them,” said Washington, who has been practicing for nearly seven years, and is close to earning his black belt.

Washington has cultivated more than a few tools for staying sharp over the years. As a graduate student researcher pursuing his PhD in the lab of Henrik Scheller at the Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI), he’s responsible for structuring his time and directing his own experiments. Pushing himself physically and tapping into his embodied intelligence through judo offers the perfect counterpoint to his analytical brain, and primes his creative thinking for solving challenging problems in his lab work.

Measuring the Microcosm

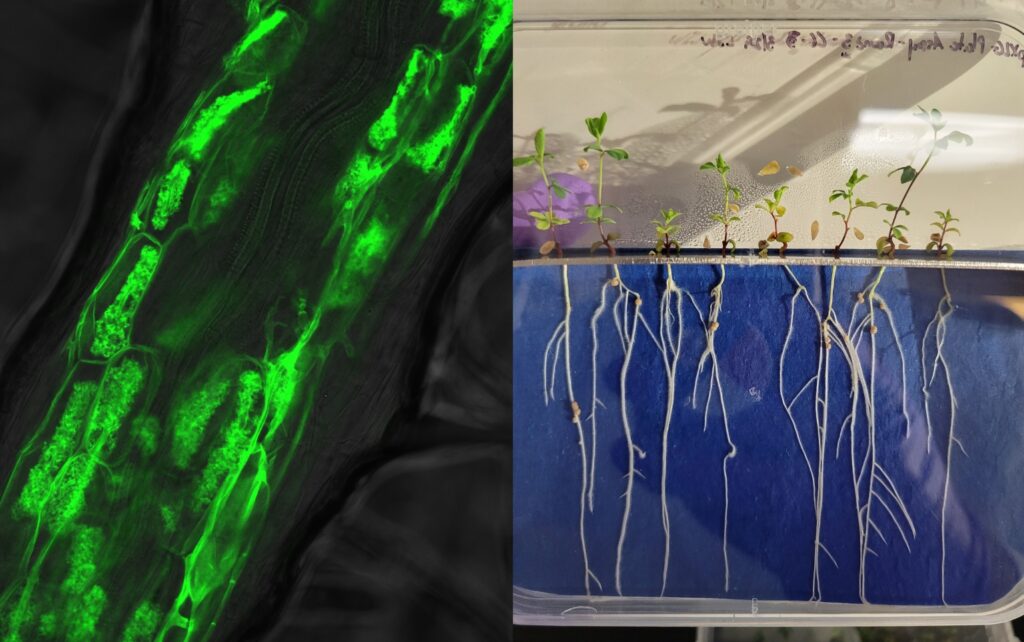

Adaptability and persistence are essential for both Washington’s tussles on the judo mat and the genetic and molecular plant biology experiments that he runs. His research aim is to decode how plant root systems establish complex symbiotic relationships with microbes. To tease apart these intricate interactions, he sets up experiments that help him observe the effect of introducing bacteria and fungi to plants grown in controlled mini ecosystems. Washington also tweaks certain genes to see how they affect the relationships plants are able to form, including signaling genes that are active while plants are interacting with microbes and genes related to cell wall formation. Developing plants with modified cell walls for improved production of biofuels and bioproducts is part of JBEI’s mission, so it’s important to understand whether altering cell wall mechanics disrupts the beneficial relationships that plants use to stay healthy.

Because plant seedlings take time to grow, and mistakes or contamination can mean starting from scratch, Washington plans his experiments with rigorous attention to detail. Iteration is also part of the process, and he has learned to start small with new ideas. He’s come to accept that there are always things he didn’t predict or account for, and that there is no such thing as a perfectly repeatable experiment with consistent conditions every time. “That’s actually a good thing,” he said.“If I only see an effect with absolutely no variation in my system, is it really a meaningful effect? Out in the world, there’s so much variation. So I’ve learned to live with a bit of messiness where acceptable.”

Washington hopes that a clearer understanding of how plants form symbiotic microbial relationships could help reduce the agricultural sector’s dependence on fertilizer and other energy-intensive interventions. But in the same way that the payoff of going to the mat each day is his primary motivation for practicing judo, Washington’s passion for tinkering with the inner workings of plants is grounded in the joy of experimentation and the perspective that follows.

“Plants have to deal with the same kinds of messiness people do–complex relationships, stresses, good times and bad–all in the context of an insanely complex system.” said Washington.

Deep Roots

Growing up in a rural, “one-stoplight” Texas town, Washington was surrounded by extensive functional and decorative gardens maintained by both sets of grandparents—and learned early how to lend a helping hand. Although the ethos of caring for living things was central to his family’s way of life,Washington didn’t always imagine himself becoming a plant biologist. Still, he knew he was interested in science. “I’ve always been a nerd and done little science fair experiments,” he joked.

As soon as he started college at Texas A&M University, Washington approached his professors about participating in research as an undergraduate. He landed a position in a plant research lab studying how maize genetics affect associations with beneficial microbes and resilience to pathogens. He started off watering corn, thinking he’d eventually transition to studying animals, then a single fact changed his course. During a lab presentation he learned about a species of grass that released chemicals into neighboring soil to kill off non-related grasses, allowing it to dominate an area. At that moment, something clicked. “I knew how to take care of plants and help them grow,” Washington recalled. “But I had never realized how dynamic they were, or their degree of agency. They can be just as interesting and charismatic as animals, and if you think about it, we know so much less about them.”

I had never realized how dynamic [plants] were, or their degree of agency. They can be just as interesting and charismatic as animals, and we know so much less about them.

From then on, Washington took every opportunity to better understand the inner workings of plant biology. With staunch encouragement from his undergraduate advisors, he rode the momentum of four years at A&M into a PhD program in the Department of Plant & Microbial Biology at UC Berkeley and moved to California. Though Washington didn’t have a definite plan for his career direction or research interest early on, he feels it worked out pretty serendipitously.

“I have the joy of finding out these specific idiosyncrasies in this chaotic, nonsensical, interdependent environment we all live in,” he said.

Cross Pollination

Washington’s activities outside the lab help provide the fertile ground for his scientific pursuits to flourish. While his judo workouts in the evenings offer a satisfying physical release, he also loves escaping into the immersive stories of video games as a way to feed his imagination and experiment with things he can’t try out in real life. These days, the fantasy tabletop role-playing game Dungeons and Dragons features more heavily in his rotation than any video game. “Because why would I be a queer PhD student who doesn’t play Dungeons and Dragons? I feel like it’s a requirement,” he quipped.

Washington’s home garden offers a particularly grounding respite from the trials and tribulations of running experiments. He works with plants all day in the lab, but like a chef cooking at home versus on the job, caring for his own plants is a completely different practice.“ The pressure is very different,” said Washington. “I’m not trying to get specific data or make anything replicable. I don’t have to baby the plants in a controlled environment. It’s more, ‘I get to make sure you flourish and do your thing.’”

With his own plants, Washington literally gets his hands dirty: Instead of handling the plants in test tubes or with ethanol-treated latex gloves, he enjoys the freedom of tearing off any dead leaves and generally connecting a bit more. “It helps what I do in the lab, because even if I’m frustrated, I never look at plants solely as test subjects. I get to appreciate them for all that they are,” he said. This perspective shows up in the language Washington uses when he talks about plants, too: For both his experimental plants and his house plants, he consistently refers to them as “someones” rather than inert “its.” “I think that’s partially from my upbringing,” he said. “My family has always been very mindful of their environment in a way that has a bit more reverence than how we were taught in school to think of plants purely as agricultural products.”

Just as gardening nourishes Washington’s approach to lab work, tinkering with plant genetics and molecular biology informs how he looks at his own plants and, importantly, how he talks about plants with others. “I have the privilege of pulling back the hood and taking a peek into how plants navigate this world in a way that a lot of other people don’t,” he said. Though Washington recognizes the limits of what he can know about a plant’s perspective from studying their physical forms, he does feel his work gives him a richer picture of their inner world, and perhaps an inkling that we have more in common with our photosynthetic friends than commonly thought. “I don’t know if intelligence is the right word,” he reflected. “But they have their own sets of needs and desires, or at least requirements that shift and change.”

In his public-facing talks, Washington enjoys giving people a window into the mind-bogglingly complex and messy plant-microbe microcosm he knows so intimately, and hopes to help them see a bit of themselves in the nature around them. He’s spoken to hundreds of people, from kindergarteners all the way through to graduate students and professionals. “If I’ve encouraged them to look at nature a little bit differently, or inspired a fifth grader to be into science in a way they weren’t before,” he said, “I think that’s a much bigger impact of my PhD than any publication.”

Written by Maritte O’Gallagher. As a communications specialist for Berkeley Lab’s Biosciences Area, O’Gallagher spotlights the people and stories behind our latest research.

Read other profiles in the Behind the Breakthroughs series.