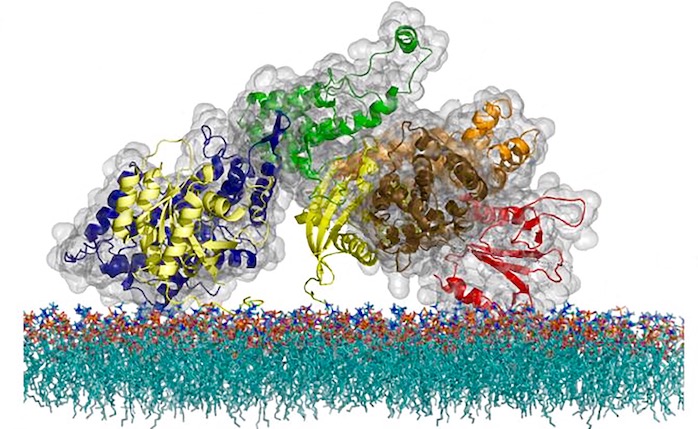

To function properly, the immune system has to be sensitive enough to detect even a single virus molecule amidst a sea of millions of other molecules, and yet discriminating enough not to be triggered by inadvertent contact with innocuous proteins. Scientist have long sought to understand how the cells involved regulate their signals in order to achieve this delicate balance.

Now, a group of Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley physical chemists led by Jay Groves, faculty scientist in Molecular Biophysics and Integrated Bioimaging (MBIB), has—for the first time—imaged the process by which an individual immune system molecule is switched on in response to a signal from the environment. Until recently, this feat was impossible because no technology existed that allowed scientists to directly monitor the activity from individual molecules in complex cell membrane systems.

But Groves’s team invented an approach using supported membrane microarrays: a technology the team has been developing for many years that uses scaffolds made of nanofabricated structures to hold cell membranes. This breakthrough led to the discovery that the immune system activation process involves hundreds of proteins suddenly coming together to form a linked network through a process known as phase transition.

Critically, the process has a built in time delay which allows the cell to distinguish a genuine receptor stimulation from background chemical noise. The work is described in a paper recently published in the journal Science.

Groves is also a professor in the department of chemistry at UC Berkeley. Other Berkeley Lab Biosciences Area authors on the paper include William Huang, a former graduate student in Groves’s lab, now a postdoc at Stanford, and John Kuriyan, senior faculty scientist in MBIB and professor in the departments of chemistry and of molecular and cell biology at UCB.