While sequencing gut bacteria from people in Bangladesh—part of a study led by a collaborator at University College London to explore the effects of arsenic-tainted water on intestinal flora—Berkeley Lab’s Jillian Banfield discovered phages, viruses that infect and reproduce inside bacteria, twice as big as any previously found in humans. Once Banfield, a faculty scientist in the Earth and Environmental Sciences Area with secondary appointment in Biosciences’ Environmental Genomics and Systems Biology (EGSB) Division, reassembled their entire genomes, she saw that these “megaphages” were 10 times larger than the average phage found in other microbiomes.

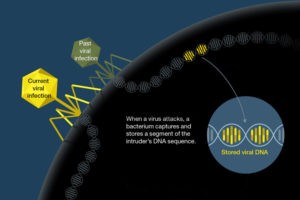

She and her colleagues found the snippets of megaphage DNA in a CRISPR segment of one type of bacteria, Prevotella, that is uncommon in people eating a high-fat, low-fiber Westernized diet. Banfield and her team named the clade of megaphages “Lak phage” after the Laksam Upazila area of Bangladesh where they were found.

The same megaphages were also found in the gut microbiomes of a hunter-gatherer tribe in Tanzania, baboons in Kenya, and pigs in Denmark, demonstrating that phages can move between humans and animals and perhaps carry disease. David Paez-Espino, a research scientist in microbial genomics and metagenomics at the Joint Genome Institute, and his JGI colleagues generated sequences in a meta-analysis related to IMG/VR that enabled identification of the baboon cohort as a potential source of Lak phage sequences.

Banfield, a UC Berkeley professor of earth and planetary science, also has a lab in the Innovative Genomics Institute, a joint UCB/UCSF initiative to widely deploy CRISPR-Cas9. With this group, she is searching through other metagenomic databases for megaphages, and hopes to learn more about how they work and whether they harbor interesting and potentially useful proteins.

Read more in the UC Berkeley News Center.