Sometimes researchers neglect to disclose inventions because they don’t seem like big “breakthroughs” in the mind of the researcher, or the invention has not been completely optimized. If your invention may have commercial value and if the essential elements can be described, you may have an invention that IPO would be able to help develop and commercialize through a patent application. The Biosciences technology commercialization team is available to discuss your idea or invention.

For an invention to be patentable, it must meet four requirements:

- It is a process, machine, manufacture of composition of matter—or any new and useful improvement thereof. Laws of nature and abstract ideas are not patentable.

- It has utility. The bar is not high; any use is typically acceptable.

- It is novel. This means it has not been previously patented, described in a printed publication, put into public use, offered for sale, or otherwise made widely available. These instances are referred to as “prior art.”

- It is non-obvious. “Non-obvious” as used here is a legal term that has specific requirements, namely: the invention is not a combination of two or more prior art references that teach or suggest the invention, and the combination has a reasonable expectation of success.

Who is considered an inventor?

An inventor on a patent is anyone who made an intellectual contribution to the invention. Unlike publication authorship, someone who performed experiments following another person’s instructions is not an inventor.

Disclosing inventions to IPO for potential patenting: Why, how, and when?

Disclosing inventions to IPO can increase the impact of your research. In addition, inventors receive 35% of net royalties from licenses to their patents or patent applications. Your employment contract also requires that you disclose to IPO all inventions you produce while you are employed at the Lab.

In many cases, an invention is not likely to be commercialized in the absence of patent protection because companies will often not invest in R&D and product or service development if they don’t have the ability to prevent other companies that have not had to make a similar investment from duplicating their products or services.

Submission of a Record of Invention (ROI) to the IP Office does not protect your invention from loss of patent rights. It is an internal document only.

Inventions should be disclosed no later than when you have finished the first draft of a manuscript describing the invention or at least two months before any type of public disclosure. (See tab below for examples of public disclosures.)

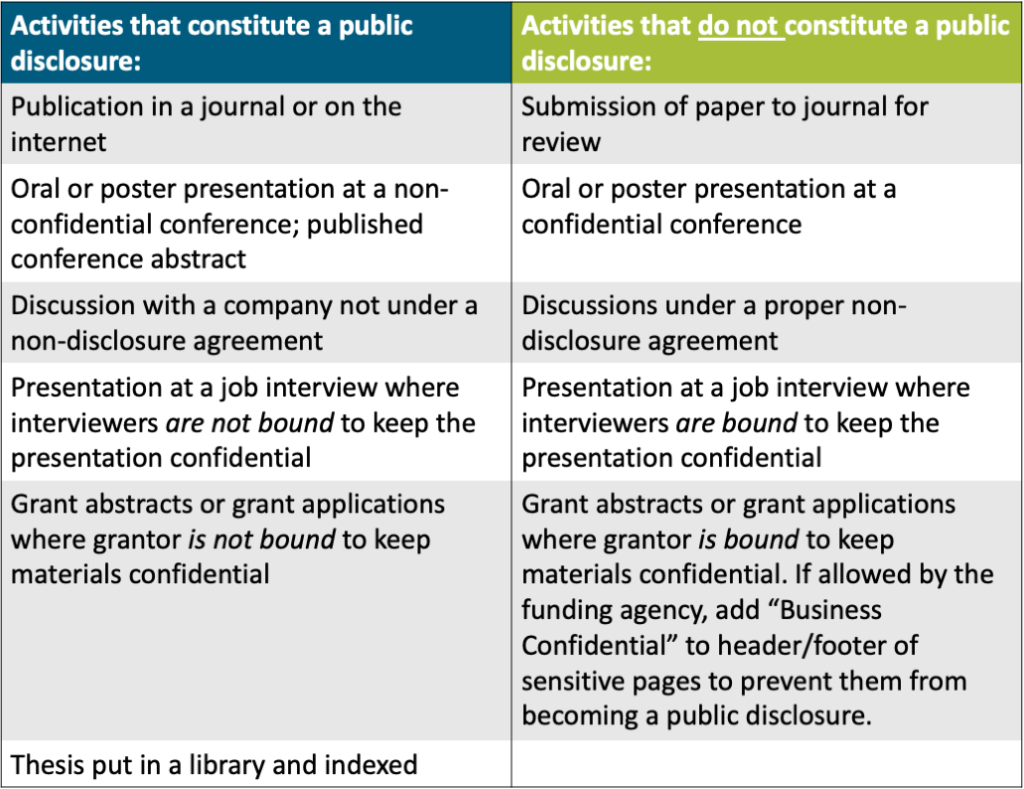

What constitutes a public disclosure that would compromise patent rights?

Who owns your invention?

The Regents of the University of California own inventions conceived by employees of Berkeley Lab that are within an employee’s scope of work at the Lab, or when the employee used Lab resources for the invention. Employees assign their inventions to the UC Regents when they sign the IP Acknowledgement form before their employment term begins.

What happens once you submit a Record of Invention?

You will receive confirmation that your submission was received. An IPO Technology Commercialization Associate (TCA)—or, for JBEI, the JBEI Director of Commercialization—will then assess the invention for commercial potential and will seek patent counsel input on patentability. The assessment will include a discussion with the inventor(s). Assessments are usually conducted within a month of submission, or sooner if an imminent public disclosure is noted in the ROI.

Which inventions should be covered by patent applications?

Some factors the TCA will consider include:

- Market size for potential products/market growth potential

- Potential profit margins

- Scale-up potential

- Strength of value proposition

- Company feedback

- Stage of development

- Time to market

- Regulatory/policy environment

- Strategic alignment with the Biosciences Area and Division goals

- Existence of, or opportunity for, future DOE funding

- Inventor interest in the commercialization process

What is a patent license?

Berkeley Lab, on behalf of the Regents of the University of California, may execute licenses which grant companies the right to exercise certain patent rights—including, in the case of an exclusive license, preventing others from exercising those rights—in exchange for certain fees and typically a royalty based on product sales. If a company first wants to explore the possibility of commercializing an invention, Berkeley Lab may grant that company an “option” to license a patent or patent application instead of an actual license. This reserves certain rights for that company but it cannot sell products or services until it has executed a license.

Why does the Lab want to license inventions?

The goal in licensing Lab technology is first and foremost to make sure inventions get out into the marketplace to benefit the public—to solve national challenges. In many cases, an invention is unlikely to be commercialized in the absence of patent protection because companies will often not invest in R&D and product development if they don’t have the ability to prevent other companies that have not had to make a similar investment from duplicating their products or services. The second goal is to get a fair return for the taxpayers, who typically fund the research, by way of investing a significant fraction of licensing income back into research.

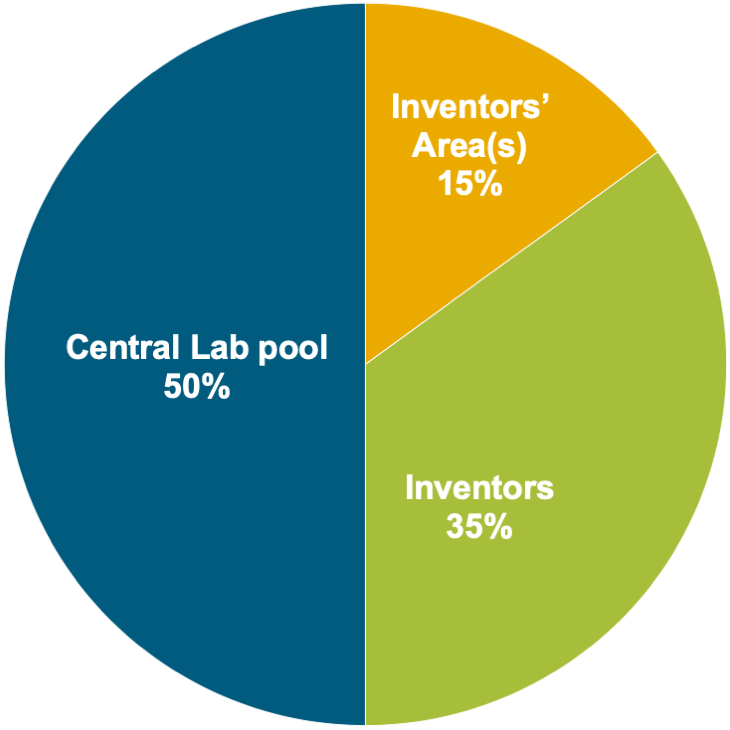

What is licensing income used for?

Net income from licenses and options (after patent costs and any other administrative fees are covered) is distributed by the following formula: 50% to the central Lab pool managed by the Directorate; 15% to the inventors’ Area(s); and 35% to the inventors. The JBEI institutional partner portion of the distribution for JBEI inventions is unique, although JBEI inventors still receive 35% of net licensing income. Licensing income is often used by the Lab to purchase critical equipment that is not allowable under other grants, to fund special projects that are of strategic importance to fundamental research, to provide match funding for proposals, and occasionally to de-risk promising inventions.