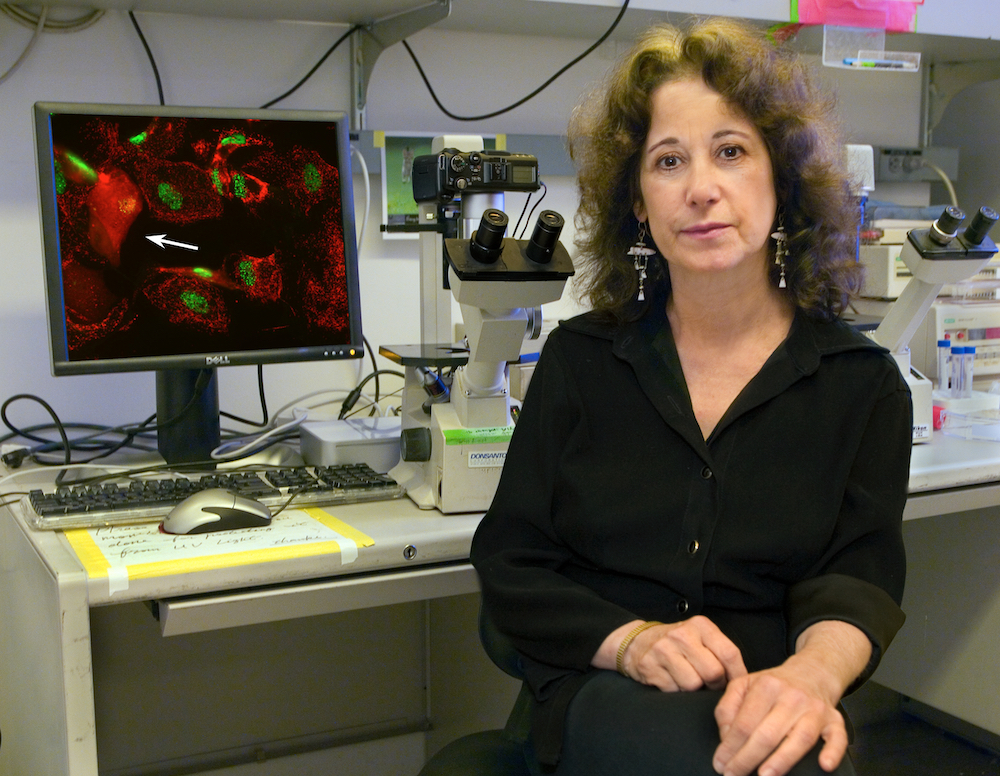

Judith (Judy) Campisi was a leader in the field of cell senescence, the natural process by which a cell stops dividing that has implications for cancer when it malfunctions, and aging when senescent cells build up. A former senior scientist in the Life Sciences Division, she was a researcher at Berkeley Lab for just over 30 years prior to leaving in 2022 to devote herself fully to her professorship at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging. Campisi died on January 19, 2024. She was 75.

Campisi was born in New York and was passionate about the arts as well as science. At a recent celebration of her life, Campisi’s brother Charles shared that she and her sister sang at the 1964 World’s Fair held in Flushing, Queens. Other attendees mentioned her guitar playing and love of dancing.

Campisi attended the State University of New York at Stony Brook, earning her undergraduate degree in chemistry and a PhD in biochemistry in the 1970s. In 1980, she began her postdoctoral research with Arthur Pardee at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School studying how the cell cycle—the different phases that a cell undergoes as it grows and divides—is regulated and how those mechanisms differ between normal and cancer cells. After four years, Campisi became an assistant professor at Boston University, progressing to associate professor in 1989.

Mina Bissell, then Director of the Cell & Molecular Biology Division, recruited Campisi to Berkeley Lab in 1990. Campisi relocated to the Bay Area and bought a house in the Oakland Hills, which was one of the first to burn during the 1991 firestorm. Her colleague, Cilla Cooper, a senior scientist in the Biological Systems and Engineering (BSE) Division, recounted that Campisi fled her home with not much more than her computer. She was grateful to be able to borrow clothes from Bissell, since both had a similarly diminutive stature (Campisi was 4’ 11”). Cooper conjectured that the event may have been the basis for Campisi’s signature wardrobe of classic solid color items like black turtlenecks.

Five years into her tenure at the Lab, Campisi published her pivotal Cell review on cell senescence and its physiological importance. If the process by which an aging cell stops dividing malfunctions, it can result in a cell that keeps dividing (e.g., cancer). And when large numbers of senescent cells accumulate in the body, they can release biochemicals that may cause inflammation and damage to healthy cells.

Pierre-Yves Desprez was a joint postdoctoral researcher with Bissell and Campisi at Berkeley Lab for five years. He observed that, in 1991 when he started, no one believed Campisi’s theory that cellular senescence was an important feature of aging. By the new millennium, however, no one disagreed with her, he added.

In 2002, Campisi joined the Buck Institute for Research on Aging as a professor and established a second lab at their campus in Novato, California. She reduced her time at the Lab in 2009 to devote more of her attention to her professorship at the Buck. Throughout her time at both of these institutions, Campisi was a leader in the field of cell senescence and defined the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. “She was devoted to understanding these phenomena and how reducing them could prevent chronic inflammation and diseases of aging,” noted BSE Division Director Blake Simmons.

Campisi was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 2018 and as a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2011. Her professional accomplishments were recognized with numerous honors and awards over her career; highlights include two MERIT awards from the National Institute on Aging (1995, 2005) and awards from the AlliedSignal Corporation (1997), Gerontological Society of America (1999), and American Federation for Aging Research (2002). She is a recipient of the Longevity prize from the IPSEN Foundation (2010), the Bennett Cohen award from the University of Michigan (2011), and the Schober award from Halle University (2013), and she was the first to receive the international Olav Thon Foundation prize in Natural Sciences and Medicine in 2015. That same year, she was honored with the International Cell Communication Network Society (ICCNS)-Springer Award to acknowledge her scientific merit and contributions to the field of cellular senescence.

Albert Davalos worked for and with Campisi for 24 years—ten of those at the Lab. Now an adjunct professor at UC Berkeley, Davalos shared, “I was fortunate to join her lab when many of her groundbreaking results occurred. It was a time of scientific interaction at the highest level.” He recalled that Campisi would arrive around noon and stay until early the next morning, creating rotating shifts in the lab so that everyone had some overlap with her. “It was a time that we couldn’t wait for her to arrive or another lab member to leave her office,” Davolos remembered, indicating that lab members would anxiously wait their turn to show Campisi their raw data and benefit from her uncanny ability to analyze their results.

Judy lived for science; it was her oxygen. She was the happiest when she was analyzing a problem.

Campisi imparted some words of wisdom to her long-time colleague: Always think three experiments ahead, or else you are behind. “Judy lived for science; it was her oxygen. She was the happiest when she was analyzing a problem,” continued Davalos. He also shared that she counseled him to read absolutely everything that pertained to his project or desired field of study. “Judy was so committed that I felt the need to share her commitment. Everyone in the lab gave everything.” he added, “I truly felt fortunate to be surrounded by such talented scientists, with Judy as our role model.”

“Without any doubt, Judy Campisi was one of the most creative, intelligent, and broadly knowledgeable scientists with whom I have interacted anywhere, any time,” Cooper affirmed. Kelly Trego, who is a senior principal research scientist at IDEAYA Biosciences, came to Berkeley Lab in 2006 as a fellow on a postdoctoral training grant that Campisi administered. Her work was a collaboration between the Cooper and Campisi labs. “Judy was incredibly focused on the science at hand,” remembered Trego. “She had a remarkable ability to challenge scientific assumptions. Many people have cited her ability to look beyond politics, and to ask hard questions of her own and others’ research.”

Cooper underscored Campisi’s enthusiasm for all of her pursuits: “She was, above all, passionate—passionate to the core of her being about science, which she lived every minute of every day.” Campisi was a knowledgeable oenophile and loved dancing, folk music, and entertaining her wide circle of friends, to whom she was devoted. “She was a wonderful hostess,” Cooper commented. Other interests of Campisi’s were ceramics and jewelry.

“It’s funny, but the most unusual and memorable thing about Judy was her ability to be absolutely present when you talked with her. It didn’t matter if the conversation was about science or any other subject,” recalled Trego. “It was so much a part of Judy to be engagingly focused and fascinated by the world. She will be missed.”

View the video of the Celebration of Life held at the Buck Institute on Friday, February 16 (program begins at 8:23). Read Campisi’s obituaries in Nature and Nature Aging.