The worlds of physics, chemistry, and biology may seem as disparate as negatively and positively charged atoms, but like those particles, when they collide, they can create something entirely new. Such a collision happened 90 years ago when researcher and physician John Hundale Lawrence left his faculty position at Yale Medical School to work with his brother, Ernest, at the latter’s new radiation laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley.

Ernest Orlando Lawrence, a pioneer in the world of nuclear physics, had just developed a marvelous new machine called the cyclotron. It could smash atoms together to produce a wide variety of elements and radioactive isotopes―ones that John Lawrence believed could be used to revolutionize the world of medicine.

That collision of emerging technologies in physics, biology, and chemistry resulted in the creation of a groundbreaking new field of science known as nuclear medicine. Over the next few decades, the Lawrence brothers and a distinguished group of physicists, biologists, and chemists worked together to use nature’s smallest unit of matter to solve some of the medical world’s biggest mysteries. Their work gave rise to many of the most effective tools for diagnosing, evaluating, and treating cancer, heart disease, neurological disorders, and other conditions. Looking back, those who were involved in the development of nuclear medicine say the key element that led to its success was the collaborative environment at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab).

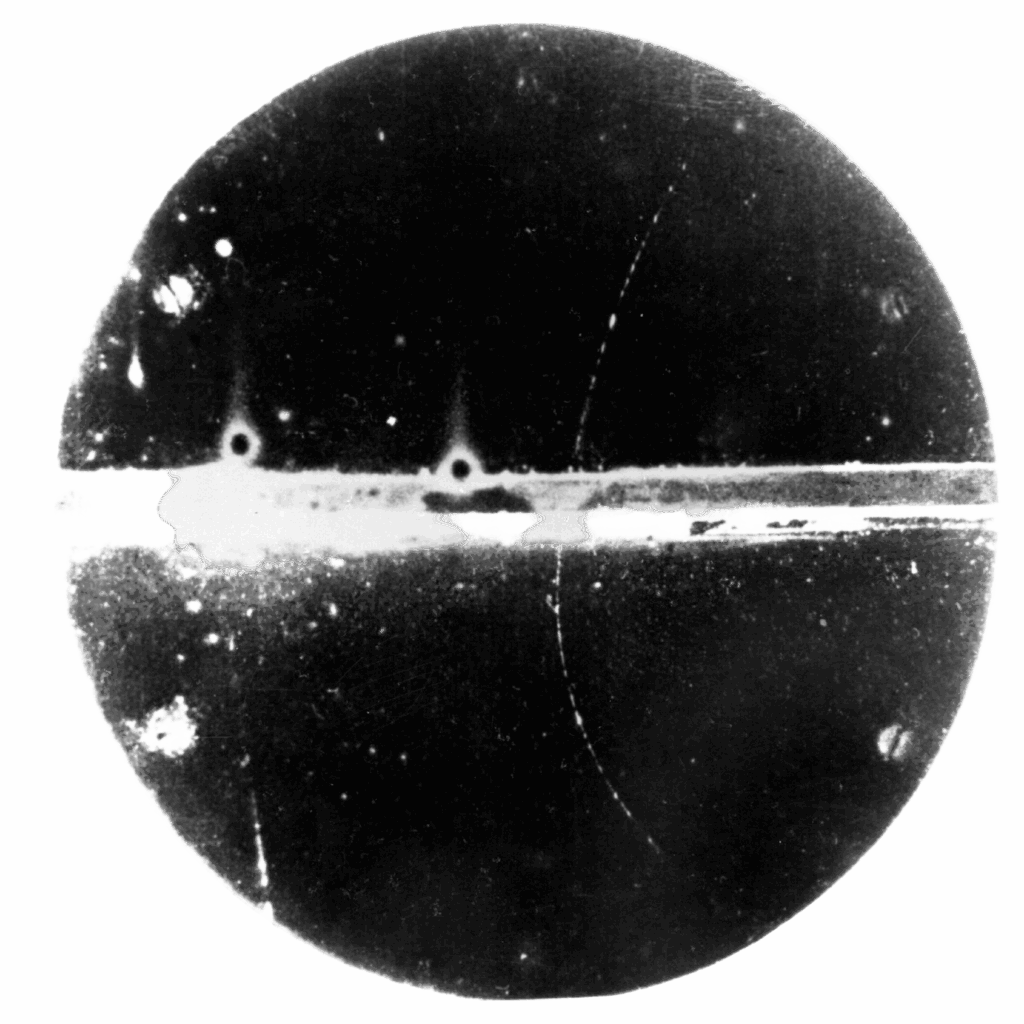

It all started in 1935 when Ernest Lawrence invited his brother, John, to visit him at the University of California, Berkeley. During his visit, Ernest took John to see the university’s cloud chamber. A cloud chamber is a particle detector used to visualize the passage of ionizing radiation. The chamber is filled with a cloud of alcohol or water vapor and when an ionized particle passes through the cloud tiny droplets form, showing the trajectory of the particle.

Seeing this phenomenon for the first time was “John’s first ‘wow’ moment in physics,” says Thomas Budinger, an affiliate scientist at Berkeley Lab who worked alongside the Lawrence brothers. Watching particles zip through the clouds and make vapor trails like tiny airplanes “made a big splash” with John, Budinger said. “It gave him two ideas: first, that radiation might be dangerous, and second, that there must be a better way to use radiation [for medicine] than just X-rays.”

At the time, humans had begun to harness the power of radiation but had little understanding of how exposure to it affected living things. In the early 1900s, doctors began experimenting with the use of X-rays to treat various ailments, with little success.

As a researcher at Yale, John had conducted a series of experiments where he exposed mice to X-rays. The electromagnetic waves did not have the hoped-for healing effects, and he wondered if other forms of radiation could yield better results. It was for this reason that he left his faculty position at Yale, packed up research materials (including his mice), and boarded a train bound for Berkeley. At one point during the cross-country train ride, the mice escaped and made their way to the dining car, sending many fellow passengers into a panic.

By the time John arrived in Berkeley, the third iteration of his brother’s patented cyclotron was already up and running. The original device, which won Ernest the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939, was a compact particle accelerator no larger than a modern smartphone. Often called “proton merry-go-rounds,” by Ernest and his colleagues, these groundbreaking machines were capable of smashing open atomic nuclei, allowing scientists to discover new elements and produce radioactive isotopes, atoms with an unstable complement of protons and neutrons.

At the time, these machines—which at first were constructed from little more than glass, sealing wax, and bronze—were the most powerful particle accelerators available. By 1938, Ernest had developed 27-inch, 37-inch, and 60-inch cyclotrons; the largest of these required a massive 220-ton magnet to operate. So the university built a large building, now known as the Crocker Laboratory, to accommodate it.

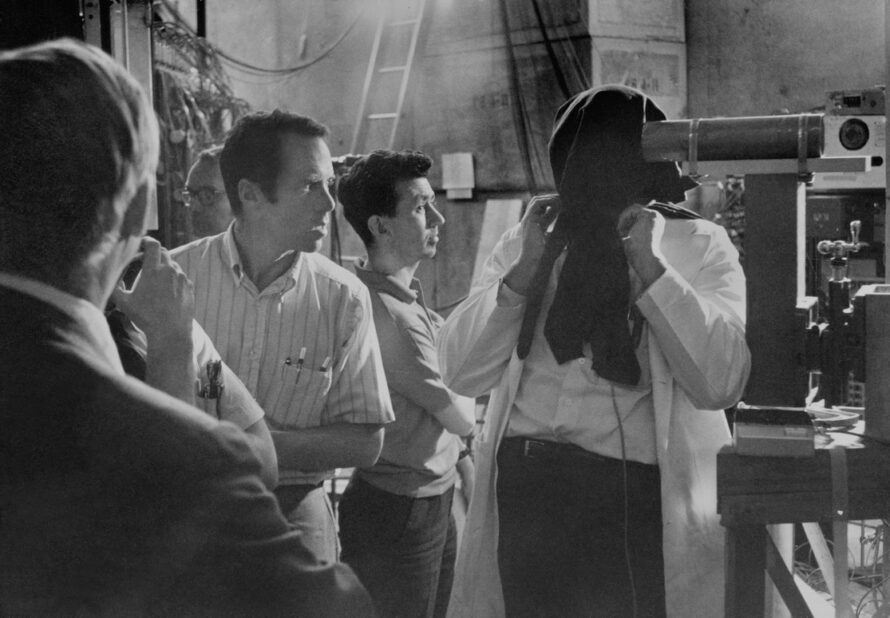

Shortly after John arrived at Berkeley, Ernest put together a team of biologists, physicists, and chemists to use his machines to discover and produce new elements and radioisotopes and see if they could be used to save lives. “John Lawrence was excited about finding isotopes that had a medical application,” said Eleanor Blakely, a biophysicist and senior scientist at Berkeley Lab. “They [John, Ernest, and their colleagues] would spend many long hours in the lab, treating patients during the day and working on the machines at night.”

“We weren’t always popular with our physicist colleagues,” John Lawrence told a reporter in 1963. “My brother and others once spent the whole night repairing the cyclotron and had just got it running again when I walked by with a pair of pliers [in] my lab jacket. The powerful magnet jerked them out and sent them smashing into the vacuum chamber window, wrecking it. I still blush when I think of it.”

Using the cyclotrons, scientists working at the lab discovered a wide variety of radioisotopes that would prove useful in nuclear medicine, including technetium-99m, carbon-14, fluorine-18, oxygen-15, and thallium-201. One of the first radioisotopes the Lawrence brothers discovered was sodium-24, which they created by bombarding rock salt with heavy ions. This radioisotope was later used by Berkeley Lab biomedical researcher Joseph G. Hamilton to determine, among other things, the speed of sodium’s absorption into the circulatory system when ingested.

Although the fruits of the lab’s research had vast applications outside of medicine, the primary focus up until the start of World War II was the treatment of rare and terminal diseases. On Christmas eve in 1936, John successfully used radioactive isotopes of phosphate to treat a patient with leukemia. This was the first time a radioactive isotope produced by a cyclotron was used in the treatment of human disease. In the years that followed, this method became the standard treatment for the blood disease known as polycythemia vera, which causes uncontrolled proliferation of red blood cells.

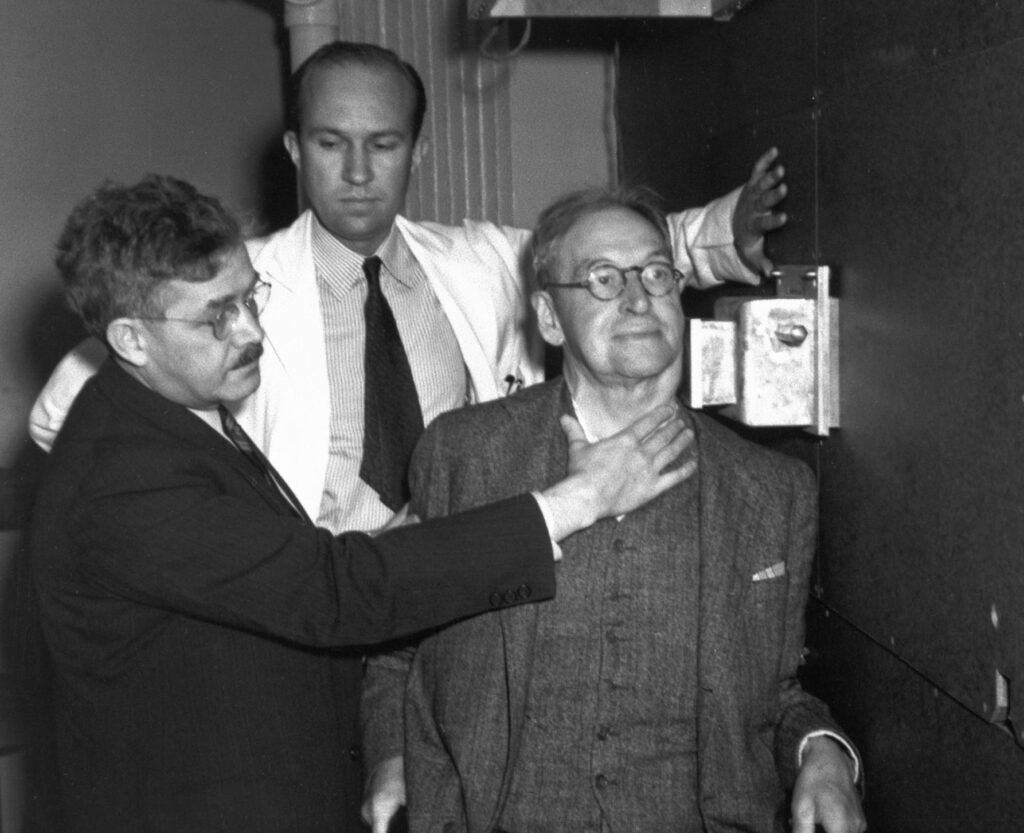

From 1938 to 1939, all physics research using the cyclotron was suspended for a full day each week so that terminal cancer patients could be treated with neutrons from the 37-inch cyclotron. Although these treatments were far less sophisticated than the treatments used today, they did extend the lives of many patients.

John and Ernest believed, quite correctly, that they could use radiation to target and destroy cancer and other problematic cells in the body. “When a tumor is treated with radiation from an external source, such as an X-ray generator, the X-rays can be imagined as a beam of very high energy photons that interact with the electrons associated with molecules that make up the tumor tissue. By knocking out electrons, the molecules become ionized, which means a neutral molecule loses an electron. Thus it becomes an ion and this ion can be equated to a damaged molecule. With enough ionization, the tumor cells will be killed,” said Budinger.

“One of the first patients that John and Ernest treated was their own mother. She, unfortunately, developed ovarian tumors and they tried to help her,” said Blakely. “When they saw someone in need, even if it was not in their own family, they would bring in a scientist who had a specialty in that discipline and then try to grow an answer.”

By this time Ernest’s lab had become a hub of innovation unlike any other. Not only did those in the lab have access to the world’s most powerful particle accelerators, but they also had the opportunity to collaborate with scientists whose areas of expertise were far different than their own. Opportunities for scientists from different fields to collaborate “were very rare back then,” said Blakely. Facilitating collaboration between physicists, chemists, and biologists wasn’t easy, but John worked hard to make it happen.

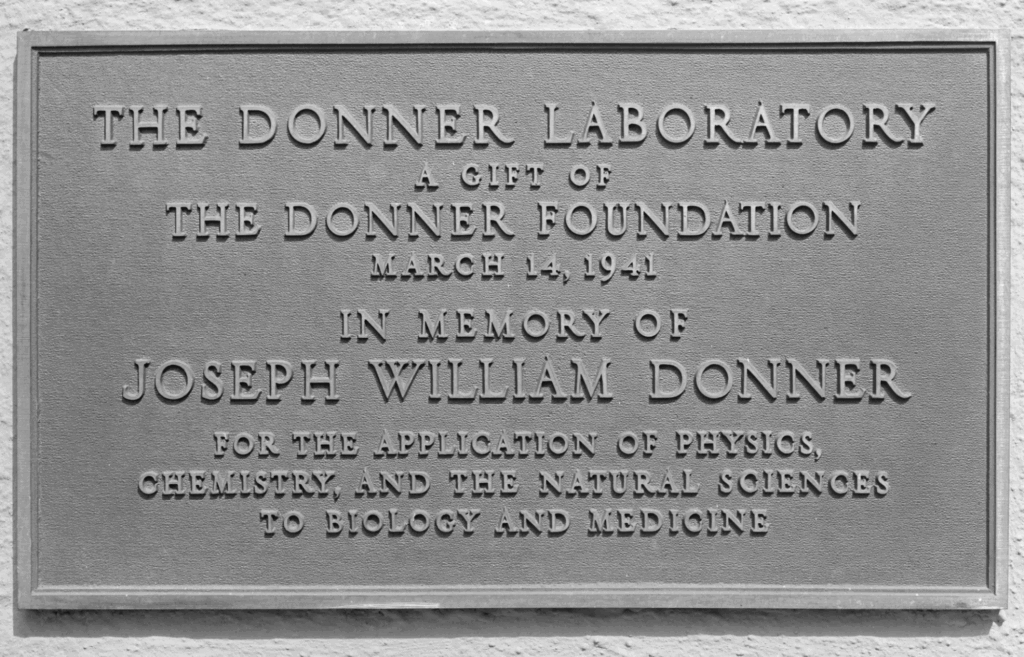

When World War II broke out, the lab’s research pivoted to projects that would support the Allied war efforts, such as the development of the first nuclear weapons, known as the Manhattan Project, as well as and the study of decompression sickness, which had become a big problem for fighter pilots. However, once the war was over, the Lawrence brothers and their collaborators returned their attention to nuclear medicine. In 1942, UC Berkeley built a new facility using money provided by William H. Donner, a wealthy industrialist who donated money to the university for work in nuclear medicine following his son’s death from cancer.

Upon completion of its construction, a plaque was placed on the Donner Laboratory building that remains there today and reads “for the application of physics, chemistry and the natural sciences to biology and medicine.” Staying true to this pledge, those working in the Donner Lab resumed their efforts to bring the brightest minds in the fields of physics, chemistry, and biology together to harness the power of radioactivity for medical purposes.

Following the war, the scientists working in Donner made many medical breakthroughs, including the use of particle beams to successfully treat acromegaly, a rare condition where the body produces too much growth hormone, causing body tissues and bones to grow too quickly, and Cushing disease, a hormonal disorder caused by pituitary tumors. They also figured out how to produce long-lived radioisotopes, which they used to label hemoglobin in red blood corpuscles, allowing them to measure the lifespan of red blood cells.

In August of 1958, Ernest Lawrence died at the age of 57. Following his brother’s death, John continued working toward their dream of using radiation to heal the sick. The fruits of the academic collaboration at what is now the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory continue to impact the world of medicine and beyond. For example, researchers at Donner developed what is now the universal standard for radioisotope safety in research and medicine. This knowledge also has been instrumental in establishing radiation guidelines for human space travel.

Additionally, researchers building upon the Lawrence brothers’ work went on to invent several medical imaging techniques, including the positron emission tomography (PET) scanner and the Anger camera; the latter allows doctors to view and analyze images of the interior of the human body and monitor the effects of radiation. These devices are still used widely today.

If it wasn’t for John and Ernest’s vision and groundbreaking work, the field of nuclear medicine might not exist. The birth of this ever-evolving field is not only the result of the Lawrence brothers’ sharp minds but also their attitude towards collaboration with others.

Having so many experts from different fields in one lab “allowed for creativity,” said Blakely. “Everyone had to make themselves useful and, in doing so, they discovered many things. It was a very exciting time to be a scientist at the Lab.”

What set the Lab apart from others of its kind, Blakely said, is that everyone working in it understood that physics, biology, and chemistry are all intertwined. When a particle passes through a cell, it creates “a symphony of action,” Blakely explained, that requires expertise in physics, biology, and chemistry to fully understand. ⬢

Written by Annie Roth, a science journalist, filmmaker, and children’s author. Research and interviews conducted by Peter Arcuni, a journalist and radio/podcast producer.

When radiobiology researcher Cornelius Tobias heard about mysterious balls of light observed by Apollo 11 astronauts, he hypothesized that they were seeing charged particles and devised an experiment—in which he played the part of the subject—to prove his theory.