When proteins aren’t rigid, but shift and bend as they work, computational and artificial intelligence (AI) approaches fail to accurately predict their shapes. This realization came as a big surprise during the most recent Critical Assessment of Techniques for Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) competition in 2024.

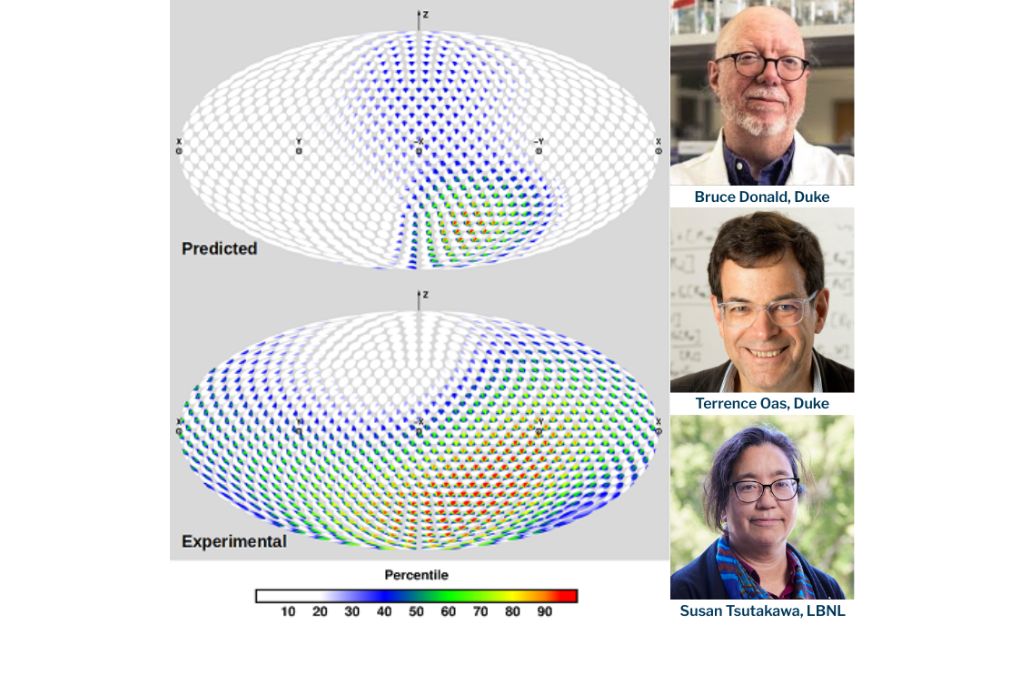

To tackle this problem, a team of researchers from Duke University and Berkeley Lab developed new statistical techniques to measure how far off a prediction is, and the individual factors in the model that could be modified to improve the accuracy. Led by Duke’s Bruce Donald and Terrence Oas, and Biosciences’ Structural Biology Department Head Susan Tsutakawa, the work was recently published in the journal Proteins.

Movement can be an important part of how proteins function and impacts how drugs interact with them. Some proteins have regions that constrain them in terms of distance but allow for full flexibility; other have engineered constrained flexibility.

“The integration of two experimental techniques—one angular and one that combined distance and rotation—provided different perspectives,” said Tsutakawa. “While both techniques captured the constrained flexibility, the two perspectives enabled more rigorous assessment.”

As the first blind benchmark of its kind, the results of this study offer a clear standard the team hopes will accelerate innovation in drug design.

Read more from Duke University.