Scientists at the Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI) are helping to speed up plant engineering with a new technology called ENTRAP-seq, which can screen thousands of transcription regulators for plants, simultaneously. Transcriptional regulators are proteins that impact how a gene is expressed; like a dimmable light switch, they can turn it off entirely or change how much of a specific product a cell makes by modulating how often the DNA is transcribed into RNA. Most of the enhanced traits we see in current crop and biofuel species are the result of transcription modulation. For example, thousands of years ago, ancient farmers bred natural variants of wheat that had higher expression of genes controlling grain size. Agricultural technology scientists would love to better wield these genetic switches, yet our understanding of them is limited, despite extensive studies of plant genomes.

“Even for the well-studied plants—where we know a ton about which genes control which things, and in many cases, how the gene works—it’s not clear how to alter gene expression to make beneficial modifications,” said Simon Alamos, a postdoctoral fellow in the Environmental Genomics and Systems Biology (EGSB) Division and at UC Berkeley and JBEI. Alamos is co-first author on a study describing ENTRAP-seq published in Nature Biotechnology. “We want to be able to use the plants’ own transcription regulators, and proteins with this activity from other organisms like plant viruses, but until now, we didn’t have a way to predict what they do or test them quickly.”

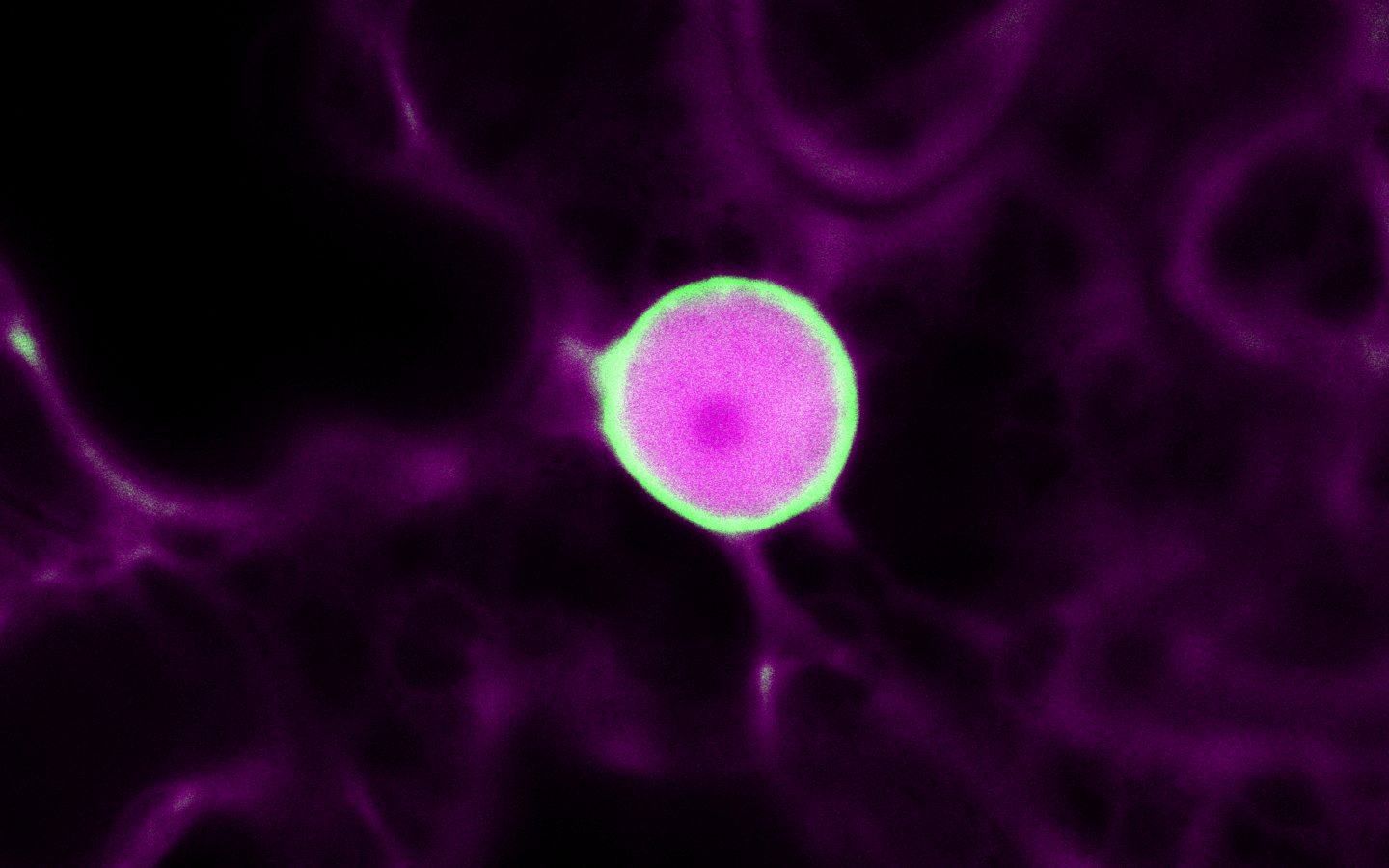

ENTRAP-seq fills this unmet need by shrinking experiments that previously required a whole plant or whole leaf down to a single cell. The process uses a plant-infecting bacterium to insert DNA sequences for many potential transcription regulator proteins into a leaf, alongside the code for an engineered target gene. The scientists make a library of thousands of bacteria, each of which contains instructions for one protein variant. Afterwards, the bacterial library is injected into a leaf and each bacterium transfers its genetic cargo to a single plant cell, so that thousands of different variants are produced by different individual plant cells.

Once the plant cell has made these components, the protein variants are able to turn on or off molecular switches inside the cell nucleus, signaling if they have activating or repressing properties. If it does have activating properties, an engineered gene will be expressed that has been specially designed to stick to magnetic tag molecules. The scientists can then use magnets to physically isolate which cells have produced the target protein, sequence the DNA inside, and match the results to the list of potential proteins they introduced.

After developing the approach, the team demonstrated its unprecedented speed for real-world investigations. They used ENTRAP-seq to study gene regulation in a transcription activator known to mediate expression of a gene that controls flowering in Arabidopsis, a plant used as a model organism for botany research. They created 350 mutant versions of the protein and quickly screened which ones could tune flowering time up or down.

“This experiment took just a few weeks. In contrast, for a previous study, our team characterized the activity of 400 plant transcription regulators, which took two people full time over two years using the conventional, brute force approach of testing things one by one,” said lead author Patrick Shih, faculty scientist in EGSB and Deputy Vice President, Feedstocks Division and Director of Plant Biosystems Design at JBEI.

Read more on the Berkeley Lab News Center.