Vibrant cities around the world are made up of a unique blend of cultures, languages, cuisines, and – as scientists recently revealed – microbes.

Nearly 1,000 scientists from around the world, including three from Berkeley Lab, collected and analyzed microbial samples from public transit stations across 60 global cities. They probed ticket kiosks, benches, and rails to see what tiny organisms like bacteria, viruses, and archaea were in residence. The team found that in most cities, the same four bacteria phyla – Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidota – are most abundant. But more interestingly, they discovered that each location also has its own distinct set of microbes.

Nikos Kyrpides, head of the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI) Microbiome Data Science group, along with Russell Neches, a postdoctoral researcher, and David Paez-Espino, a research scientist, used an extensive JGI database to investigate viruses detected in the samples.

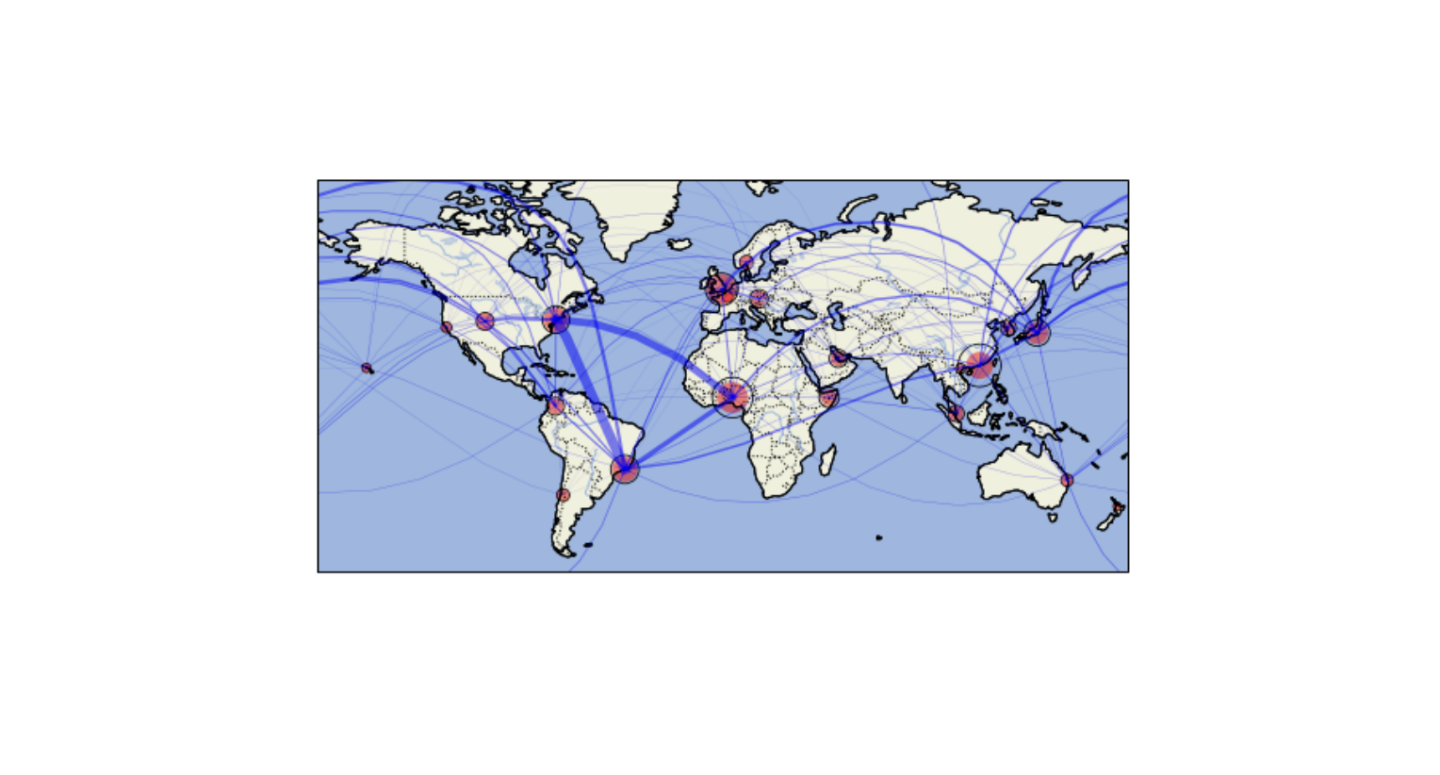

The JGI scientists took the nearly 5,000 viral genome samples collected by the larger consortium of scientists involved in this work, known as the International Metagenomics and Metadesign of Subways and Urban Biomes, or MetaSUB, and compared them to the database. Neches and Kyrpides then set out to map the diversity and global distribution of the viruses.

“The integration of all these data in a single database is a key resource for the research community which provides a reference point for comparing viruses identified from new samples,” Kyrpides said.

In addition to mapping microbial signatures, scientists discovered over 10,000 new viruses and bacteria, hinting at the vast world of microbes that is yet to be understood.

Public health officials can now use these microbial maps to keep track of virus and bacteria levels over time. “It’s like a census,” Neches said. “This can inform on where public health resources can best be allocated to benefit all of us.”

Read the Cornell Press Release.

This Science Snapshot appeared in the Berkeley Lab News Center.