Scientists hoping to elucidate the complex anatomy of mammalian brains and other organs have for years been limited by a frustrating paradox: The most powerful microscopes can see details at the nanoscale—features thousands of times smaller than the width of a human hair—but only if the specimen sits incredibly close to the lens, typically less than a millimeter. The traditional solution has been to mechanically cut large pieces of intact tissue into thin slices. However, this process introduces distortion, tears, and missing pieces—particularly when scientists first embed the specimen in a soft hydrogel to make the tissue transparent and gently expand it to make details easier to see. The damage makes it impossible to reconstruct a complete, accurate 3D model of the specimen.

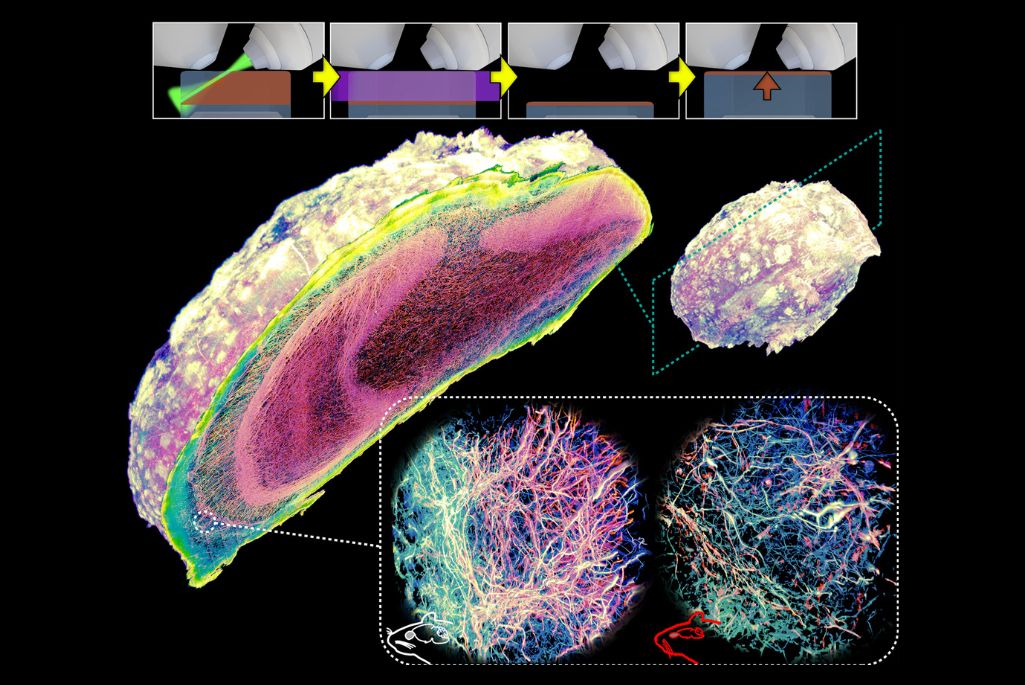

Now, a team led by Srigokul “Gokul” Upadhyayula, a faculty scientist in the Molecular Biophysics and Integrated Bioimaging (MBIB) Division, and Ruixuan Gao, an assistant professor at the University of Illinois, Chicago, has developed an elegant alternative they call Volumetric Imaging via Photochemical Sectioning (VIPS). In place of a blade, the method uses a thin sheet of light to trigger a chemical reaction within the illuminated volume, breaking down a precise layer of tissue. The molecules that make up this dissolved layer diffuse away, revealing a fresh surface underneath, ready to be imaged. The process repeats automatically, layer after layer, forming a complete three-dimensional dataset.

“Our new approach delivers a solution to a long-standing roadblock in optical microscopy: Until now, it simply wasn’t possible to see nanoscale details deep inside intact, whole-mount tissues, no matter how much time, money, or computing power you invested,” said Upadhyayula, who is also an assistant professor and Scientific Director of the Advanced Bioimaging Center at UC Berkeley. “Using VIPS, we have shown that it is possible to perform super-resolution imaging of intact, whole-mount specimens at petabyte data scales. This technology opens the door to exascale biological imaging, enabling ambitious efforts such as mapping the complete wiring diagram, or connectome, of the human brain.”

In an article featured on the cover of Science, the researchers detailed how they used VIPS to image two complete adult mouse olfactory bulbs at nanoscale resolution, allowing for comparative analysis of axons and myelin sheaths in wild-type versus neurodegenerative mice. This enabled them to visualize an intriguing centripetal pattern of demyelination of axons in the neurodegenerative bulb.

(Credit: Gao laboratory, University of Illinois Chicago; Upadhyayula laboratory, University of California, Berkeley)

A complete mouse brain imaged with VIPS would generate petabytes of data, so the team created an open-source software toolkit called PetaKit5D to process and analyze these massive datasets. This effort was supported by a Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) award to Upadhyayula. By redesigning every stage of the pipeline for high-performance distributed computing, PetaKit5D can cut processing costs by more than an order of magnitude and make ultra–high-resolution imaging projects, such as mapping whole brain structures, practically achievable.

In addition, the team received an allocation through the Berkeley Lab Director’s Reserve to use National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) resources to process data published in the Science paper.

What makes VIPS particularly powerful is its versatility. It works with various tissue preparation methods, integrates with existing microscopes, and can theoretically image specimens of unlimited size. The researchers envision studying entire human brain regions or other organs with cellular and subcellular precision, something previously unimaginable.

Challenges remain, however, including how to uniformly and densely label biomolecules deep within large specimens, where to store all that data, and how to make sense of the trove of information. Still, VIPS represents a crucial step forward, effectively removing specimen size as a barrier to high-resolution imaging. It’s the difference between examining individual trees and being able to map an entire forest, tree by tree, branch by branch, leaf by leaf—all without disturbing a single twig.