Richard “Rick” Schwarz dedicated much of his four-decade career as a research scientist to understanding how tendon cells control collagen production and cell proliferation. A retiree affiliate in the Biological Systems and Engineering (BSE) Division at the time of his death in May 2025, he never really retired and was working with UC Davis to arrange animal trials on the tendon growth factor he discovered.

Born in 1947 in Manhattan, Schwarz spent his childhood in Washington Heights and then Scarsdale, New York. After graduating from high school, he bought a 1960 black Volkswagen Beetle and made his way to UC Berkeley, where he studied biophysical chemistry, met his future wife, Lavinia “Vinnie” Gilbert, and graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1968. His tendon research began with his doctoral project at Harvard, where he was mentored by Paul Doty. In a 2021 interview with Avanti Research, he recounted having to choose between two projects: one studying early development using freshly fertilized sea urchin eggs and the other studying collagen expression. “Sea urchins were an unpredictable source of biological material and the scientists working with them were always working late into the night because of a delayed shipment. So, I chose to study collagen differentiation,” he said.

In 1976, Schwarz joined Berkeley Lab as a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Mina Bissell, now a retiree affiliate, formerly Biochemist Distinguished Scientist, in what was then the Cell and Molecular Biology Division. He completed a nine-month Royal Cancer Society fellowship in London in 1980 and followed that with three years at Jackson Labs in Maine. In 1983, he returned to the Lab and rejoined Bissell’s group.

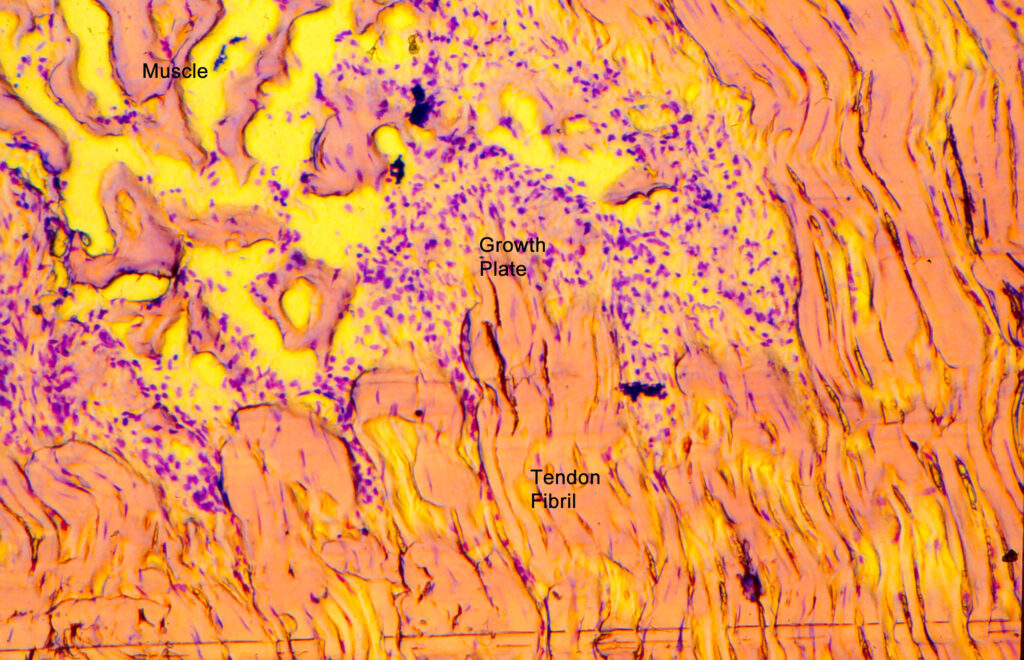

Collagen, the fibrous protein the body uses to build tendon (basically, a collagen rope that links muscle to bone) and ligament (similar, but links bone to bone) tissue, is produced in only small amounts in adults. Studying chicken embryos, Schwarz identified a molecule that guides the formation of tendons and ligaments. The gene that expresses the protein component of this signaling molecule turned out to be highly conserved among species. Schwarz postulated that this protein-phospholipid molecule could be administered to adults who have, say, gotten tennis elbow playing pickleball, to spark healthy tendon growth in the same way that happens during embryogenesis.

In a touching obituary prepared by his loving family, they shared that, because he worked with chicken embryos, Schwarz hatched chicks for his kids’ Easter baskets every few years, which the family would raise until they were mature enough to join friends’ flocks. A father of three, Schwarz was frequently described by colleagues as the “lab dad.” “[He] gave parenting advice to every new parent in the lab, always delivered with a mix of wisdom and warmth,” recalled Jamie Inman, a research scientist in BSE, noting that Schwarz’s counsel was often exactly right.

He enjoyed working with his hands and figuring out puzzles. “Rick was always the first to roll up his sleeves and fix whatever needed attention in the lab,” reflected Antoine Snijders, formerly a senior scientist in BSE, now at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. “His hands-on approach and technical know-how kept everything running smoothly, and we all knew we could count on him when something broke down.” In his leisure time, Schwarz took up wood working and built a strip cedar/fiberglass canoe. He also liked to cook, garden, and be entertained with movies, music, books, and sports.

In 2019, Schwarz formed a company, SNZR LLC, to move his tendon growth factor into clinical trials. In his last two months, he passed his research on to his son-in-law, Jonathon Holt, who has created a non-profit foundation that will work to take it to human trials, continuing Schwarz’s passion and legacy.