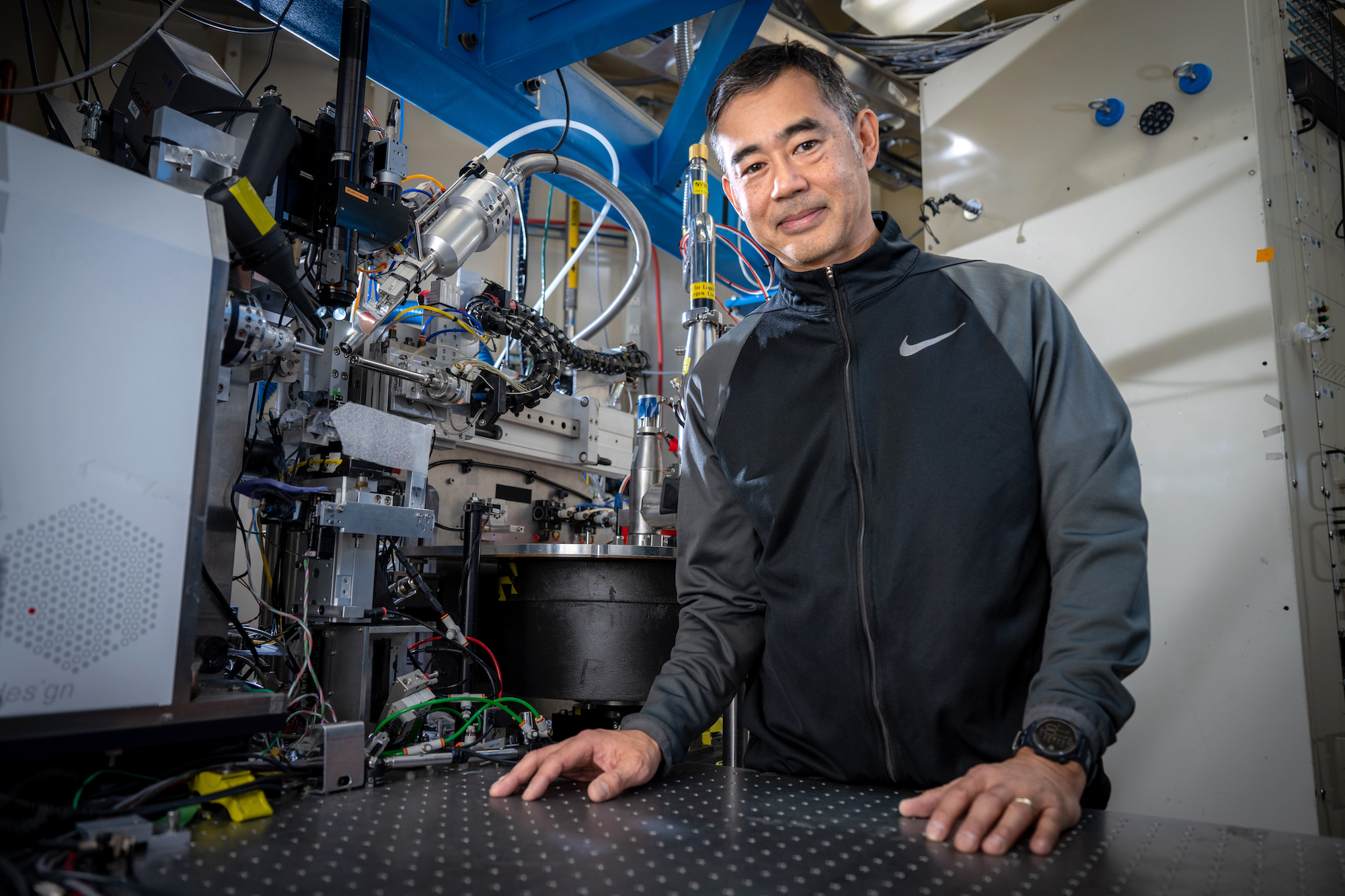

For scientific engineering associate Anthony Rozales, the workday begins before the sun rises. His shift overseeing the protein crystallography beamlines at the Advanced Light Source (ALS), a user facility at Berkeley Lab, is from 5 AM to 1 PM. It’s critical for many of the ALS users to run their experiments around the clock, so the team divides the day into three shifts.

While some people might find Rozales’s early morning shift grueling, for him it’s ideal. His drive home takes less than half the time than it would during normal commuting hours, and he’s left with an open afternoon to do what he loves most. Years ago, Rozales began running as a hobby after he ran in a race with a few friends. So most days of the week, after his shift ends and he makes it home, Rozales usually turns right around and leaves again, this time on foot.

“There are so many stresses that we deal with at work and with family,” Rozales said. “When I’m running, I really can’t think of anything except my breathing. It becomes meditative.”

The Power of Light

A member of the Berkeley Center for Structural Biology (BCSB) team, Rozales works with scientists from around the world to provide technical support for their experiments, which are designed to help them better understand the molecular structure of proteins. Proteins are known as macromolecules because, in the grand scheme of things, they’re much larger and more complex than smaller molecules, like hormones or water.

Through understanding the arrangement of atoms in a sample, protein crystallography provides scientists insight into its function and how it interacts with other molecules. This information is critically important to solve a vast array of challenges that range from human health to environmental. “It’s exciting to work on these projects,” Rozales said. “I know that this work is helping society, it just feels good.”

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Rozales and his team worked with academia and pharmaceutical companies to decode the structure of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Samples were processed around the clock and, over time, the data generated by the BCSB team contributed to structural information about the virus that was critical to drug development and therapy breakthroughs.

At the ALS, bright beams of X-ray energy are directed to about 40 beamlines, six of which are managed by the BCSB team. On these beamlines, protein crystal samples are maintained at cryogenic temperatures. Powerful electromagnetic radiation hits the crystal and, while most of the energy passes through, some intercepts parts of the crystal and scatters in a different way depending on its contents. The resulting spots of X-ray light are collected and analyzed with computer software. Like a human fingerprint, every protein has a unique structure so this scatter map provides scientists with a more precise understanding of its unique molecular makeup.

Rozales helps to both set up experiments and ensure that things run smoothly on the beamline. Once a user is scheduled for beamtime, samples are sent to the ALS where Rozales and his team receive them and then walk the user through how to use the beamline from afar.

In recent years, many aspects of the BCSB beamlines have been automated or configured to operate remotely. So instead of manually arranging the samples for experiments as users had to do in the past, Rozales and the team use a graphical user interface (GUI) that controls the robot that, once programmed, takes care of this step automatically. “But things don’t always work right,” Rozales said. “That’s why I’m here.”

In Motion

Using his hands to make and repair things is something that Rozales has always enjoyed. Growing up in Southern California, and later the Bay Area, he spent time with his father tinkering away in the garage on various projects. This led Rozales to an industrial technology program at San Francisco State University and a role with a semiconductor company immediately following graduation. After a few years working in the hardware industry, Rozales pivoted to his role at Berkeley Lab in 2003.

When not working on the beamline, Rozales still finds plenty of projects around the house to keep his hands busy. One of his sons is approaching legal driving age and recently they’ve been working together to repair a car that will be his to use, pending a passing score on the driving test. And when his hands need a break, Rozales laces up his running shoes.

About 10 years ago, a group of friends decided to run in a local race that involved training beforehand. Although Rozales had never been into running as a hobby before, he decided to sign up. What started for Rozales as an excuse to get active and be social evolved into a full-blown obsession. “I was never a runner before that first race, but afterward, I realized that it was a great way to be active and just kept going,” he said.

The group signed up for their next race together, another 5K which equates to just over 3 miles. They continued signing up for opportunities to run together, graduating to a 10K, a half-marathon, and eventually, a marathon (26.2 miles). “We just kept saying, let’s see if we can go a little further,” Rozales remembered with a laugh.

Work-Life Optimization

Most of the time, Rozales goes out for a run five days a week, with the other two intentionally reserved as recovery days. He’s noticed how much this hobby helps his mental health and ability to focus at home and on the job. “When I’m running, I think about how to optimize everything, from my body movements to my breathing,” Rozales said.

And he’s applying that awareness and perspective to his role on the beamline. Receiving samples and executing the users’ experiments is a process that Rozales is continually looking to optimize and improve. One of the steps in his routine for shipping samples back to the user after they’ve been analyzed involves removing reagents that were added for the experiment.

The samples are sent in a dewar, a container about the size of a barbeque’s propane tank, which must be picked up and emptied of its liquid nitrogen before being sent back to the user. Previously, the team used a rope and pulley system to tip the dewar, a time-consuming process that often held up the line on busier days. Rozales realized that instead, he could lift the container on his own in an ergonomically-safe way that was much faster. “It’s not for everyone, but because I’ve become so fit from running, I can do it,” he said. He has since taught his technique to others at several ALS beamlines. “I always find myself thinking about how my job can be done better and faster,” he said.

At home, running permeates into Rozales’ family life too. His two teenage children recently joined their school track teams and, after finishing his daily post-work run, Rozales stops by their practices to volunteer as an assistant coach. Despite the impressive distances that he’s already covered, Rozales is feeling ready to go for the next level: later this year, he will be running a 100K race in hopes to qualify for a 100-mile ultramarathon race.

Out of the group of friends that he began running with, only one continues to run with Rozales at these longer distances. But he’s made plenty of new friends along the way. “It feels so healthy,” Rozales said. “I’m going to keep doing it until I can’t.” ⬢

Written by Ashleigh Papp, a communications specialist for Berkeley Lab’s Biosciences Area.

Read other profiles in the Behind the Breakthroughs series.