Laura Fernandez likes to think there are two types of people in the world: bakers and cooks. “Bakers are very exact. Their measurements matter; they think on a gram-to-gram basis,” she said. “Cooks are figuring it out as they go: tasting, adding a bit of salt, going on feel.”

While Fernandez considers herself a cook by nature, she’s embraced the precision of baking in her current role as the senior fermentation engineer and safety liaison for Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Biofuels and Bioproducts Process Development Unit (ABPDU). The ABPDU serves as a testbed for emerging technologies that tweak the metabolic pathways of microbes so they can transform raw materials—like plants and waste—into sustainable everyday products. Fernandez executes external collaborations with companies, helping them to scale up their experimental fermentation processes and explore how lab-bench prototypes can become commercial reality. Most of her collaborators are start-ups ramping up the bioeconomy with next-generation biofuels, biochemicals, and other bioproducts—with the end goal of decarbonizing transportation, food, manufacturing, and other industrial sectors.

“They give us a recipe, and we try to recreate that and think through some of the challenges they might see at scale,” said Fernandez.

Much of Fernandez’s day-to-day hinges on meticulous efficiency, with her main task being to zero in on a predictable, replicable formula for taking her collaborator’s idea to the next level. But she finds ways to balance that with her iterative, cook-style creativity, both on and off the job.

“Fermentation, in general, is a mix of both art and science. There are so many unknowns you’re attempting to control in this evolving, growing culture,” said Fernandez.

Seeds & Starters

Though the suburbs of Cincinnati, Ohio, where she grew up weren’t always filled with engineers or eco-activists, Fernandez followed subtle nudges towards science and sustainability. When she was eight years old, her dad brought home a pin that said, “Save the bees!”

“I didn’t know bees needed saving,” Fernandez reflected. “But it just made sense to me; that the world is not infinite.” Similarly, when a high school physics teacher inquired whether she’d ever considered becoming an engineer, it spurred Fernandez to double down on her studies in chemistry, physics, and math. She then went on to major in chemical engineering at the University of Louisville.

Starting sophomore year, Fernandez interned at a large-scale plastics manufacturing facility. While producing plastics ran counter to her environmentalist ideals, she saw the value in learning what she didn’t want to do and developing transferable skills. When she came across a blog article on the alternative protein movement—using biochemical engineering to create meat- and dairy-like products from more sustainable inputs—Fernandez recognized an opportunity to apply her experience towards a purpose she was passionate about. She focused her remaining coursework on environmental biology and stayed an extra year to complete her master’s degree at the University of Louisville with the Conn Renewable Energy Center.

She dipped a toe in academia while writing her master’s thesis on a key step in the classic biorefinery framework: encouraging the release of sugars from biomass for microbes to eat during fermentation. Though research was better aligned with her values, it felt too unstructured to pursue as a career. Searching for a fruitful stopgap, she crossed the continent to accept an internship in the quality-assurance lab of a large-scale winery in Sonoma County, California.

Her new daily routine involved testing batches of wine for factors like acid and alcohol content. Seeing fermentation up close helped her build a thorough understanding of the process and which factors to optimize for that would prove key for her role at the Lab later on. And though the nuts and bolts of the work relied heavily on her engineering expertise, she also discovered the more artisanal, subtler aspects of fermentation. Uncontrolled variables can actually become pivotal; the surrounding environment, for example, provides the distinct taste or quality associated with Belgian beer, San Francisco sourdough, or Kentucky bourbon. “You have to be kind of in touch with the universe,” said Fernandez. “Trust it a little bit.”

Still, she didn’t love the boom-and-bust cycle of intense activity followed by a lull during the off-season. Recognizing that the wine business was yet another path that wasn’t for her, Fernandez reached out to one of her university professors working in the area, who passed along a job opening for a fermentation engineer position at the ABPDU.

All the ingredients synergized: her deep understanding of fermentation from the winery paired perfectly with the pre-fermentation sugar extraction process she’d studied for her master’s, and experience on a safety project with the plastics company prepared her to take on a secondary responsibility as the ABPDU’s new safety liaison.

Booze to Biofuel

In her new role at the ABPDU, Fernandez was managing nearly the same process she learned at the winery, just condensed and intensified. Whether making wine or biofuel, the basic elements of fermentation are the same as they were back when humans first started manipulating the process to alter foodstuffs in the neolithic era: add microorganisms (like yeast, bacteria, or algae) to sugar water and let them eat the sugar to create a desired byproduct. But while fermenting grape juice to get alcohol takes several months, most ABPDU fermentations take only two to five days. And Fernandez exercises a bit more control.

“With wine, part of the fun is letting nature do its thing, but at the ABPDU, we want more predictable results,” Fernandez said. “Our reactors are more than just vessels. We control things like pH and oxygen availability.”

Another key difference is that the engineered metabolisms of the microbes used at the ABPDU allow them to make byproducts other than alcohol, such as jet fuel, pharmaceutical ingredients, or food proteins. One success story involved an algae designed to produce oil, which can then be made into bioplastic.

But to compete with petroleum-based plastic, which can be produced continuously, classic batch-based fermentation needed to level up. Berkeley-based company Pow.bio had developed an experimental, and quite complex, approach to achieve continuous fermentation, which involves adding feedstock and removing completed product steadily without the need to start a new batch. Fernandez’s team was able to successfully prototype their process, which ultimately will be used to create alternatives to petroleum-based basics.

Sustainable Growth

Fernandez has juggled multiple responsibilities since starting at the ABPDU in 2020, and no one else has a job quite like hers. Beyond the hum of her day-to-day fermentation projects, her work as the safety liaison involves streamlining processes and helping staff to work smarter, not harder. For example, when she first started, the process of prepping feed media involved a considerable amount of brute force.

“We were lifting heavy buckets, and eventually someone tweaked their shoulder,” said Fernandez. “I knew there was a better way to do it.” So she implemented key adjustments, including using smaller buckets and a platform ladder instead of a step stool, to better accommodate people of various sizes and strengths. “The world is not fundamentally built for women, so I find sometimes we have to be more resourceful.”

Fernandez also has had the chance to support the long-term growth of the bio-industry through a collaboration with UC Berkeley’s bioprocess engineering master’s program. She runs three hands-on sections for lab-based courses and serves as the project manager for the collaboration as a whole. The challenge of making the experience engaging for such a diverse group of students has helped her tap into a part of herself that loves teaching. “The students reliably ask me questions that I don’t know the answers to, so I find new things to teach myself,” she said.

A Well-Balanced Brew

Fernandez isn’t afraid to learn new things off the job, either. In 2023, she and her boyfriend trained for and ultimately completed a half-ironman race—a trifecta of 1.2-mile swim, 56-mile bike ride, and 13.1-mile run—all within a tight time window on a single day.

“I maintained a good attitude throughout the whole race day which I’m pretty proud of,” said Fernandez. The sense of accomplishment from finishing the race helped Fernandez expand her idea of what she was capable of. “Not much sounds hard after you swim, bike, and run for eight hours straight. It’s fun to impress yourself every once in a while!”

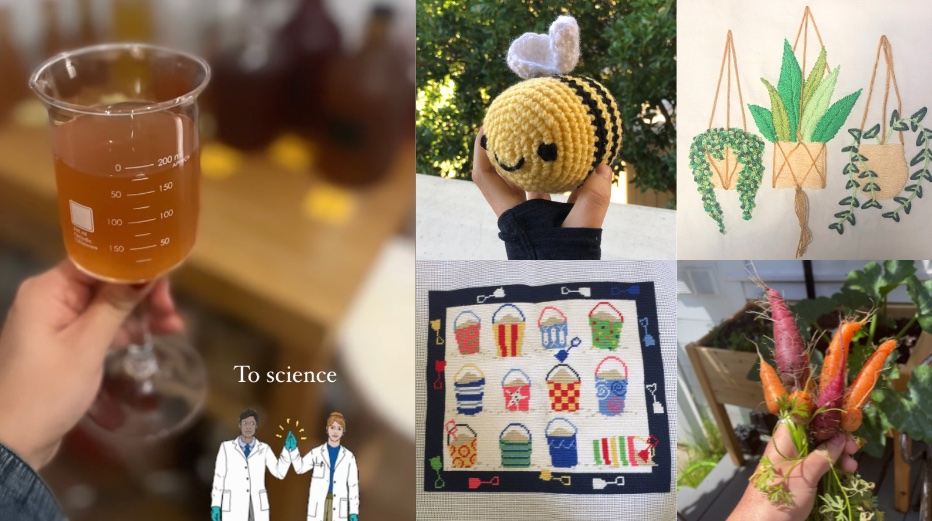

Triathlon training also provided a counterbalance to other parts of her life. “Work keeps me on my toes—it’s very mentally engaging and unpredictable,” said Fernandez. “Training offered a space to follow the plan, do the workout, and not think about much but what was directly in front of me.” While the practice of turning her brain off balanced out her professional life, the physical release complimented some of her other more sedentary hobbies, like home fermentation and crafting.

Fernandez savors turning her professional expertise towards the artisanal with assorted home fermentation projects, from kombucha brews to sourdough bread. The freedom to take her time and work the same process through multiple iterations activates her cook-like instincts to grasp subtleties and seize opportunities to stray from the original recipe. “Home fermentation projects also smell better!” she quipped.

Fernandez insists that her other tactile pursuits, from knitting and crocheting to fine-tuning her garden setup, are closer to the part of herself that chose to be an engineer than one might suspect.

“Crafting is a way I build confidence in figuring things out,” said Fernandez. While crafting, unlike many male-coded activities like building with Lego bricks, is not generally thought of as a pre-engineering activity, knitting and coding, for example, are not that different. Both involve working with loops, detail-oriented problem-solving, and fixing past mistakes. “I’m just using my hands instead of a computer.”

Evolving Cultures

Crafting and engineering—with a mix of perspectives from cook-types and baker-types—both have a role to play in building the bioeconomy. And while Fernandez doesn’t think any one project will save the world, she does believe in providing a testbed for innovation, building fundamental knowledge of industrial fermentation and its emerging applications, and investing in systems and infrastructure that offer alternatives to relying on petroleum.

“People think it will never change, because petroleum dominates the world,” Fernandez said. “But we built a system around the petroleum industry. Our cars work on petroleum because that’s what we built them to do.”

And though she’d love to raise awareness about the rich history of fermentation and its power as a tool for bioproduction, it’s not all about science and technology, either.

“Crafting, and more generally, creativity, are necessary causes. And education and communication are so important for building a culture around sustainability and producing things differently,” said Fernandez. “A new world is possible, and it can be different without feeling that different.” ⬢

Written by Maritte O’Gallagher. As a communications specialist for Berkeley Lab’s Biosciences Area, O’Gallagher spotlights the people and stories behind our latest research.

Read other profiles in the Behind the Breakthroughs series.