A human’s health is shaped both by environmental factors and the body’s interactions with the microbiome, particularly in the gut. Genome sequences are critical for characterizing individual microbes and understanding their functional roles. However, previous studies have estimated that only 50 percent of species in the gut microbiome have a sequenced genome, in part because many species have not yet been cultivated for study.

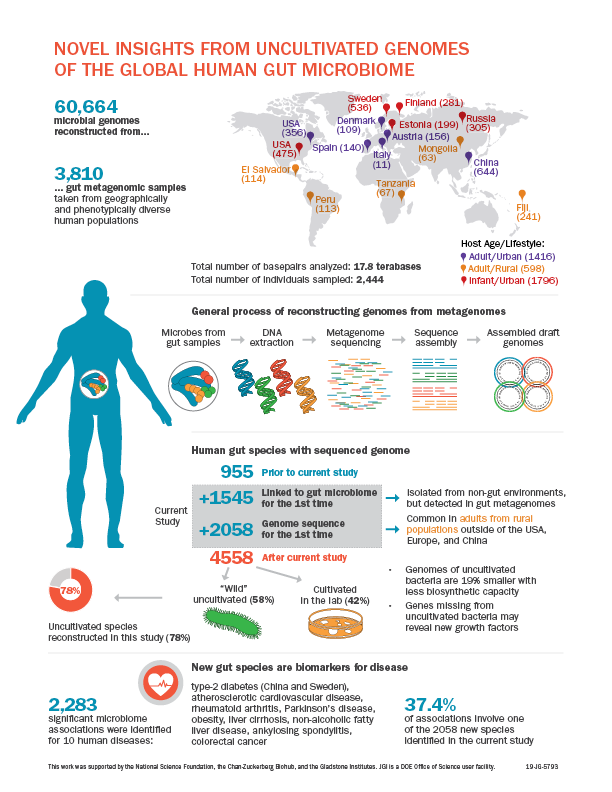

In Nature, researchers at Berkeley Lab, the Gladstone Institutes, and the Chan-Zuckerberg Biohub presented nearly 61,000 microbial genomes that were computationally reconstructed from 3,810 publicly available human gut metagenomes, which are datasets of all the genetic material present in a microbiome sample. The metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) included 2,058 previously unknown species, bringing the number of known human gut species to 4,558 and increasing the phylogenetic diversity of sequenced gut bacteria by 50 percent.

This work helps answer the question of why certain microbes have not been cultivated in the lab. Scientists have previously used metagenomics and single-cell genomics to discern the specific metabolic capabilities of uncultured microbes present in environmental samples. “However, many environmental communities are poorly studied, so it’s not clear whether or not uncultivated organisms are really uncultivable,” said Stephen Nayfach, a scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Environmental Genomics and Systems Biology (EGSB) division and the study’s first author. Read more in the Berkeley Lab News Center.