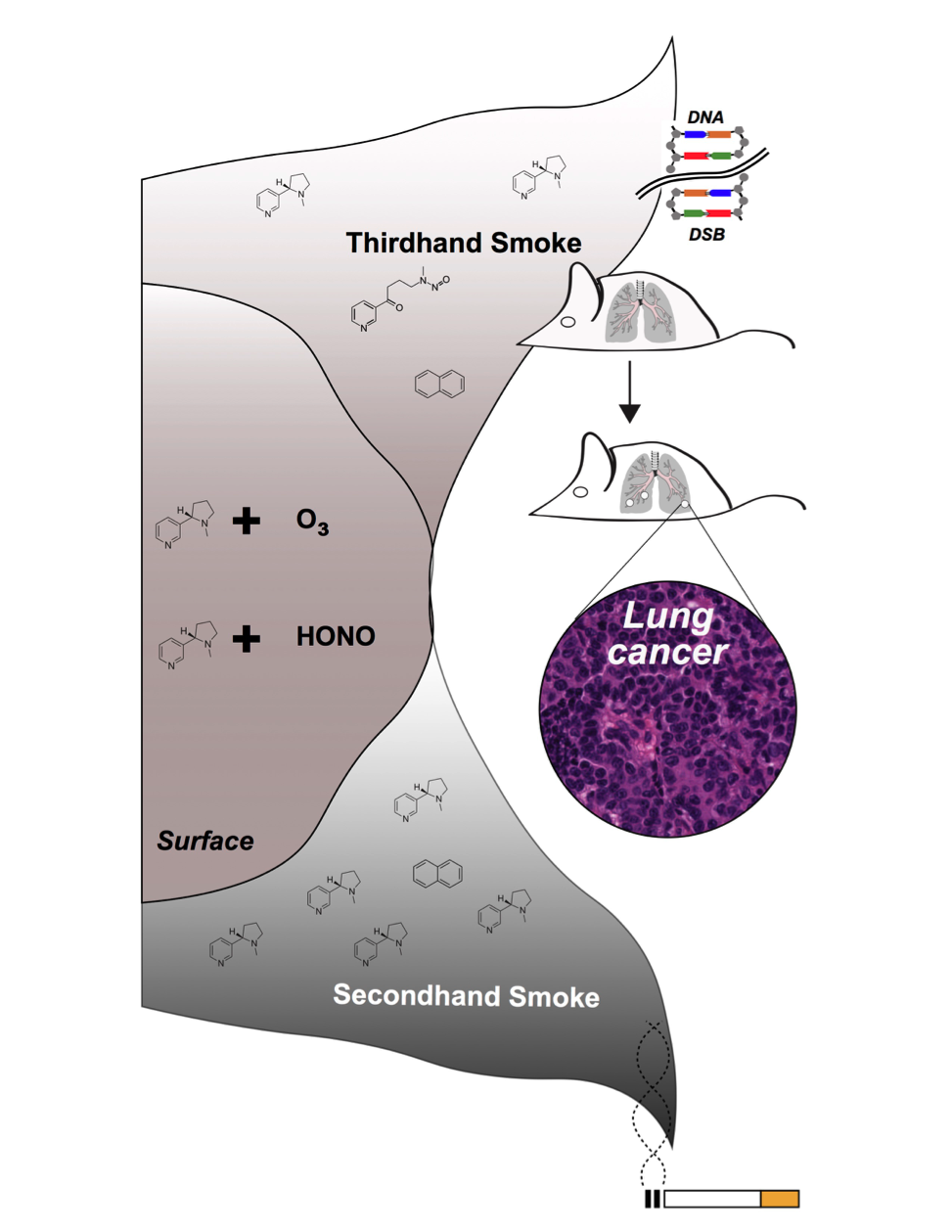

Cigarette smoke contains myriad compounds that are known mutagens and carcinogens, and the health risks associated with active smoking and secondhand smoke are well established. Nearly 10 years ago, researchers at Berkeley Lab identified another potentially hazardous source of tobacco exposure: “thirdhand smoke,” the toxic residues that linger on indoor surfaces and in dust long after a cigarette has been extinguished.

A team led by Antoine Snijders, Jian-Hua Mao, and Bo Hang in Biosciences’ Biological Systems and Engineering (BSE) Division first reported in 2017 that brief exposure to thirdhand smoke is associated with low body weight and immune changes in juvenile mice. In a follow-up study published recently in Clinical Science, the researchers and their collaborators at the UC San Francisco School of Medicine determined that early thirdhand smoke exposure is also associated with increased incidence and severity of lung cancer in mice.

Field studies in the U.S. and China have confirmed that the presence of thirdhand smoke in indoor environments is widespread, and traditional cleaning methods are not effective at removing it. Because exposure to thirdhand smoke can occur via inhalation, ingestion, or uptake through the skin, young children who crawl and put objects in their mouths are more likely to come in contact with contaminated surfaces, and are therefore the most vulnerable to thirdhand smoke’s harmful effects.

Thirdhand smoke contains chemicals in cigarette smoke that are deposited on indoor surfaces. Some of these chemicals interact with molecules from the air to create a toxic mix that includes potentially cancer-causing compounds. In this study, researchers have shown for the first time that thirdhand smoke exposure in early life induces lung cancer in mice.

In the new study, an experimental cohort of A/J mice (a strain susceptible to spontaneous lung cancer development) was housed with scraps of fabric impregnated with thirdhand smoke from the age of 4 weeks to 7 weeks. The dose the mice received was estimated to be about 77 micrograms per kilogram of body weight per day – comparable to the ingestion exposure of a human toddler living in a home with smokers. Forty weeks after the last exposure, these mice were found to have an increased incidence of lung cancer (adenocarcinoma), larger tumors, and a greater number of tumors, compared to control mice.

To further investigate how thirdhand smoke exposure promotes tumor formation, the team performed in vitro studies using cultured human lung cancer cells. These studies indicated that thirdhand smoke exposure induced DNA double-strand breaks and increased cell proliferation and colony formation. In addition, RNA sequencing analysis revealed that thirdhand smoke exposure caused endoplasmic reticulum stress and activated p53 (tumor suppressor) signaling.

The physiological, cellular, and molecular data indicate that early exposure to thirdhand smoke is associated with increased lung cancer risk. However, “future studies will need to be conducted using population-based models to address individual variations in response to thirdhand smoke,” noted Mao, a senior staff scientist.

Hang, a staff scientist, and Yunshan Wang, a postdoc in Mao’s lab, were co-first authors on the paper detailing the work. Hugo Destaillats and Lara Gundel of the Energy Technologies Area (ETA), who were the first to report the potential dangers of nicotine in thirdhand smoke, were also co-authors on this study. The work was supported by the University of California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP), Berkeley Lab’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Center for Research Resources.

“The evidence that is being gathered, studied, and presented here clearly supports the link between thirdhand smoke and a variety of health concerns that the TRDRP has been supporting now over several years,” said Anwer Mujeeb, Program Officer for the Thirdhand Smoke Research Consortium of the TRDRP.