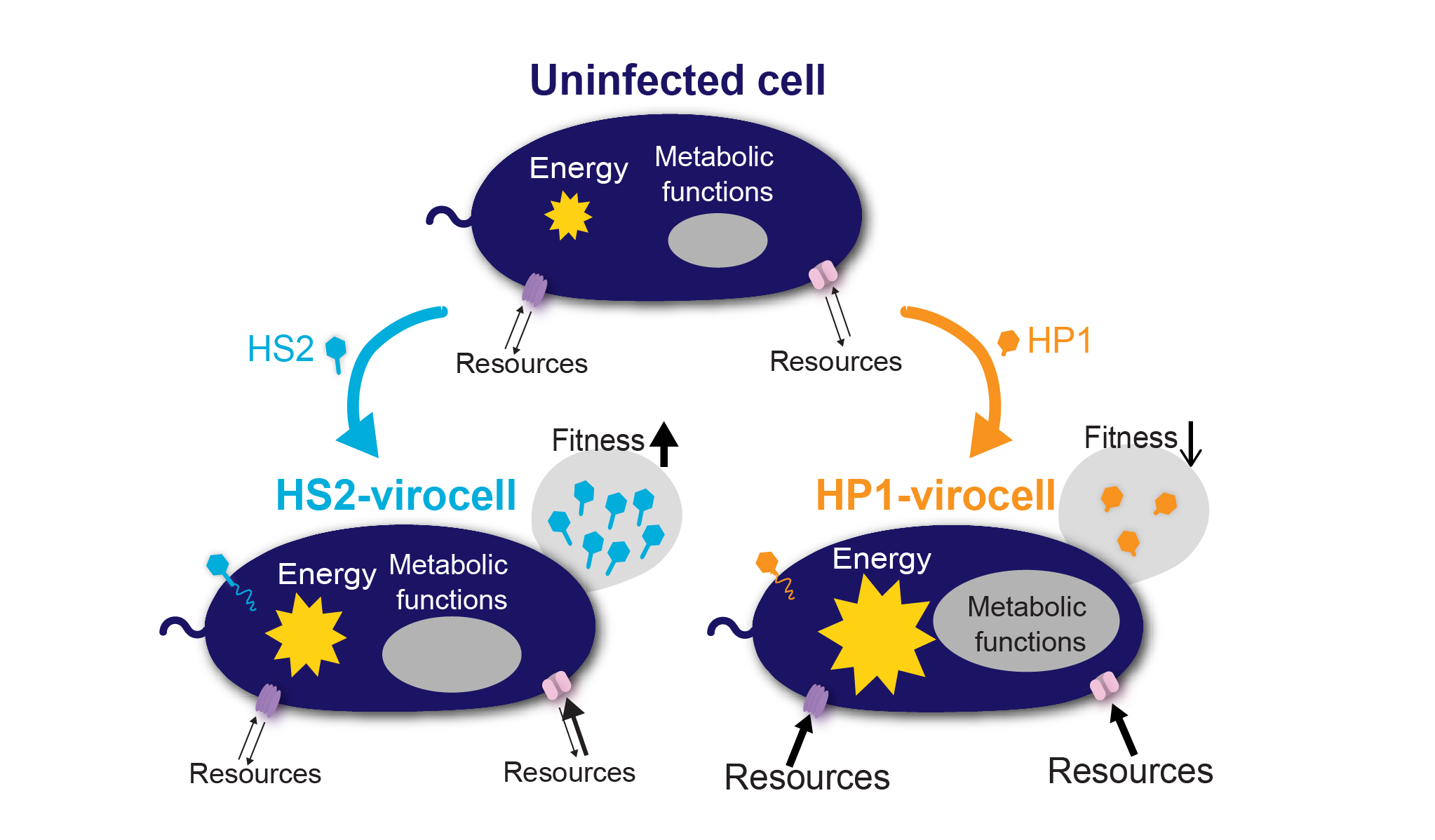

How a cell behaves as virocell largely depends on the infecting virus and the genomic similarity between host and virus. Pseudoalteromonas was infected with two unrelated viruses: siphovirus PSA-HS2 and podovirus PSA-HP1. The infections transformed the same bacterial host into two very different virocells. (Figure by Cristina Howard-Varona)

If it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck, so the adage goes, it must be a duck. But if the duck gets infected by a virus so that it no longer looks or quacks like one, is it still a duck? For a team led by researchers from The Ohio State University and the University of Michigan studying how virus infections cause significant metabolic changes in marine microbes, the answer is no.

Little is known about virus-infected microbial cells that are transformed into virocells, and how the outcomes of these infections can affect the interactions within their ecosystems. Their research was enabled in part by the Facilities Integrating Collaborations for User Science (FICUS) collaborative science initiative between the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Joint Genome Institute (JGI), a DOE Office of Science User Facility located at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), and the Environmental Molecular Science Laboratory (EMSL), a DOE Office of Science User Facility located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL).

Read more on the JGI website.